Installer Usability

Dear reader,

Writing this article, I have no idea who you are. This might be the first article you’ve ever read about FreeBSD; or you might already be well-versed with the system because you wrote half of it after all. I do not have the slightest idea about the hardware you are reading this article on either; it might not even have been made yet, and I do not know if you have any disabilities or impairments.

Well, this is exactly the kind of challenge the installer of an Operating System has to deal with. It somehow needs to work in every situation, while being appealing or usable for everyone, possibly even anticipating future evolutions. It is a tough task.

An installer is often the first time a prospective user interacts with a given system, and it is therefore responsible for the first impression. At the same time, a power user may not have to use the installer very often on personal hardware — basically when setting up a new system — but may want to automate the installation of dozens of systems for various tasks, or even for customers when deployed in a professional context.

All things considered, these different aspects can be approached under a single perspective: usability. But what is usable? And more importantly, how usable is the FreeBSD installer in comparison to other systems?

State of the Art

Evolution of Microsoft Windows

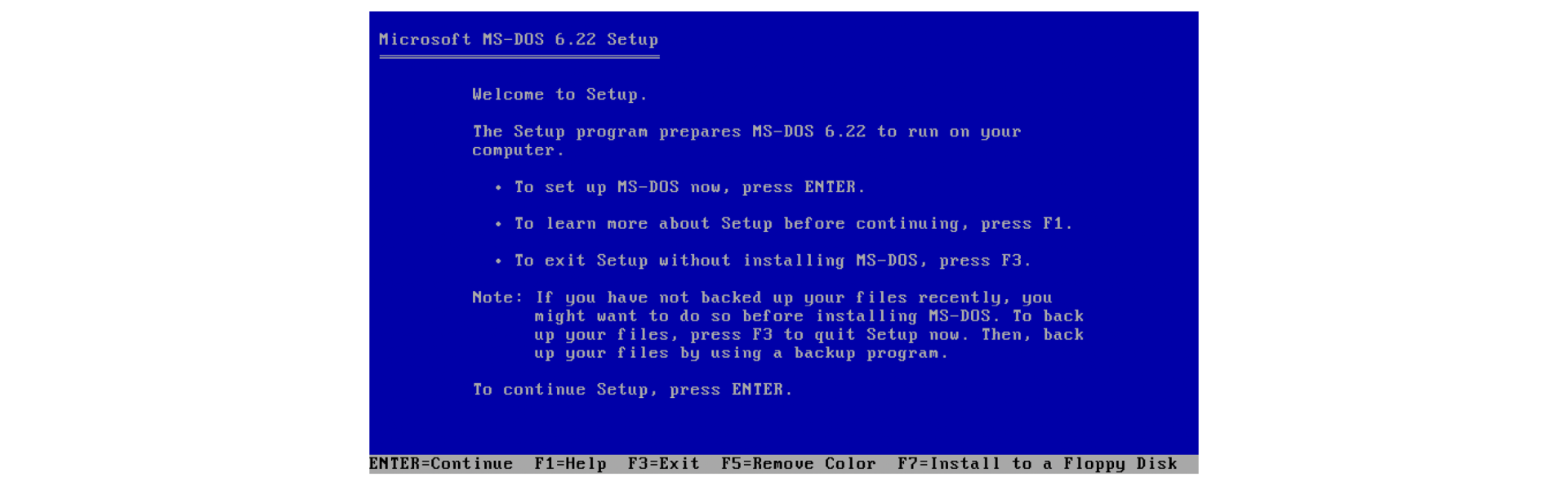

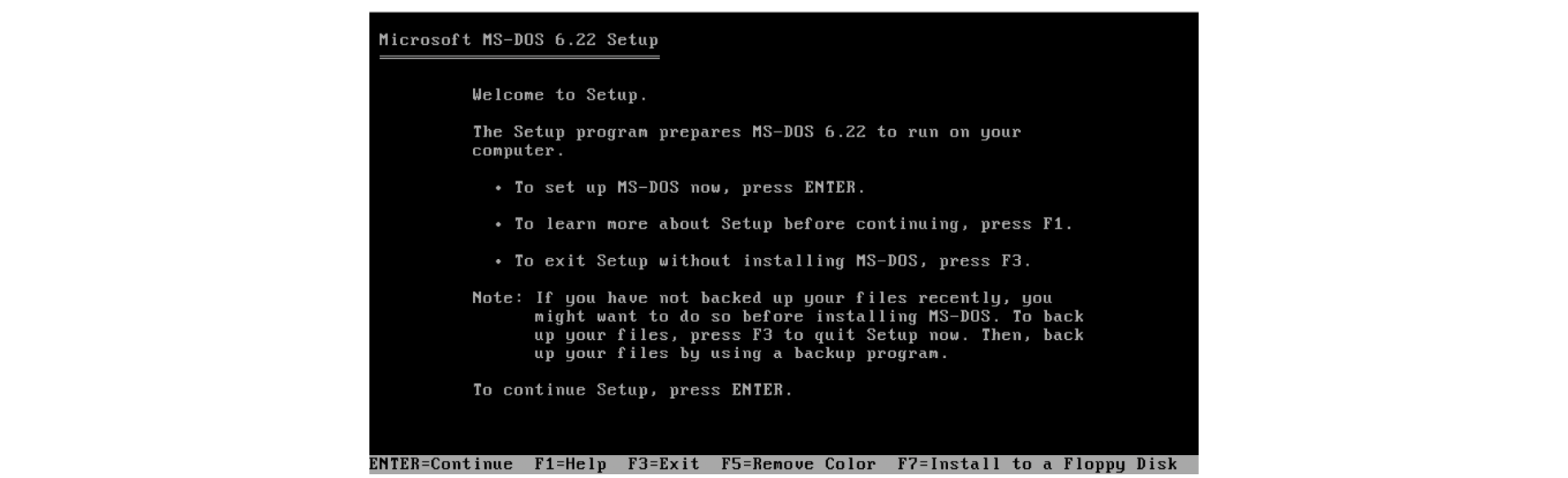

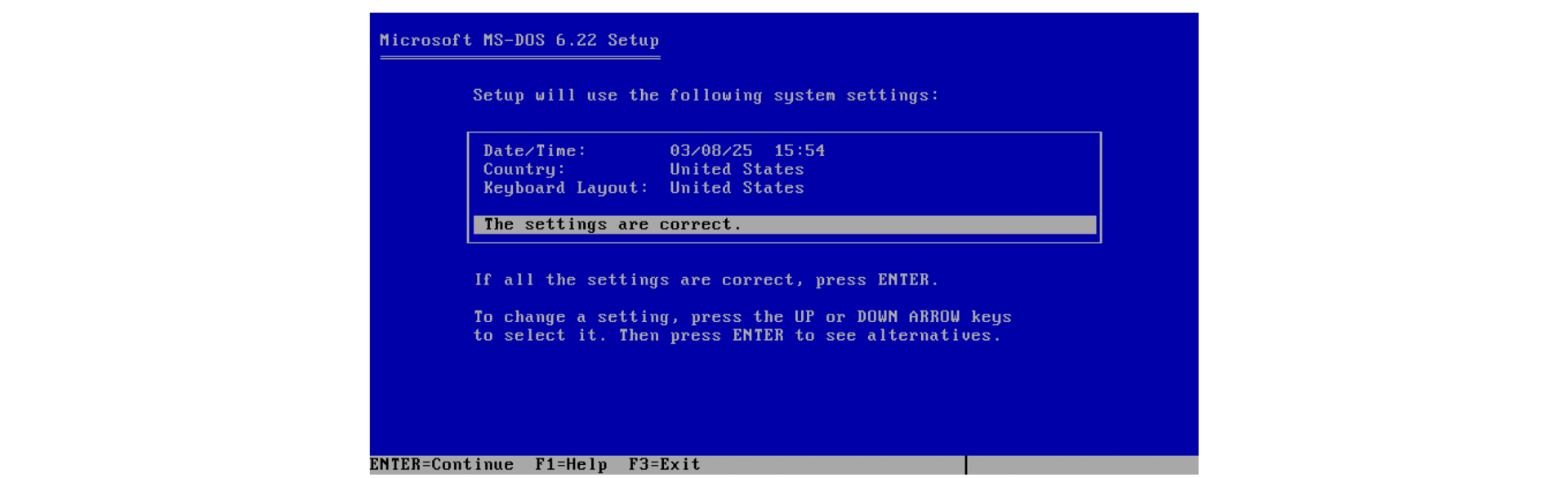

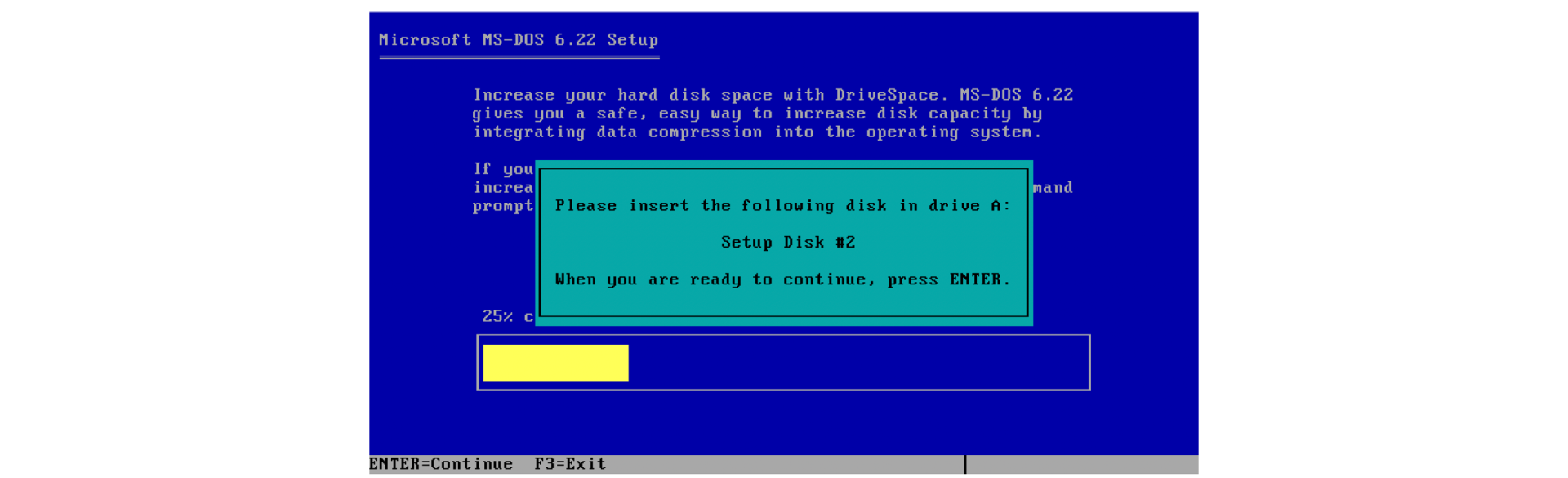

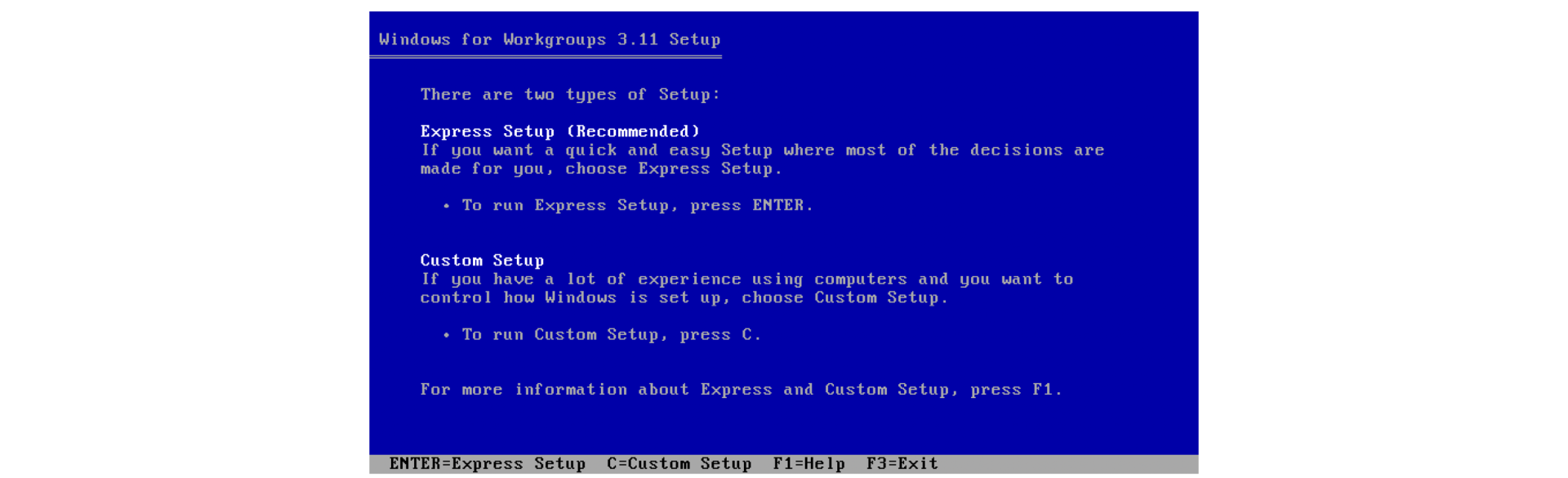

Installers go back a long way. My first contact with installers takes me back to the introduction of a computer into my household around 1989. At the time, this usually meant installing MS-DOS, and then installing Windows 3.1 on top. Obviously, installing MS-DOS was performed in text mode (80-columns VGA) but it was possible to disable colors — which doubled as a crude accessibility feature: high contrast.

While performed in text mode, the installation process already featured a progress bar, and specific highlighting for user input.

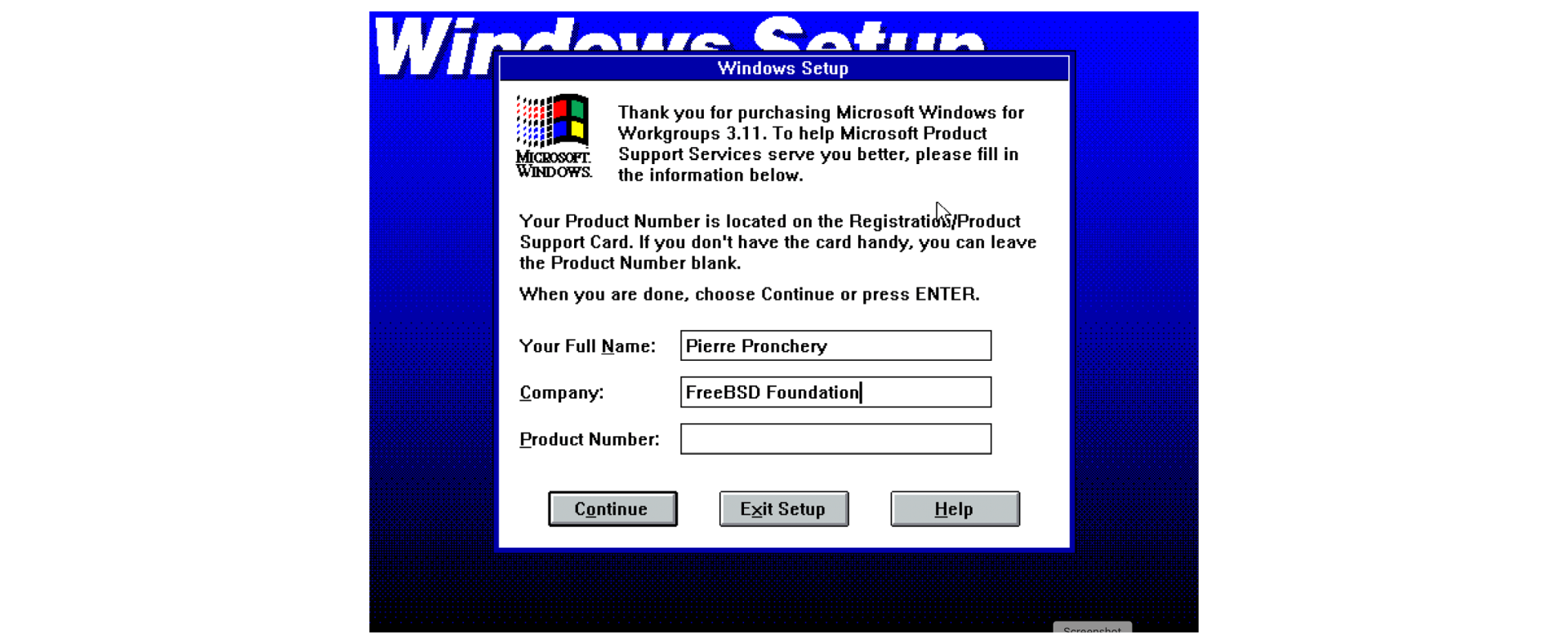

On the other hand, the installer for Windows (here in version 3.11) was quickly able to use its own graphical interface for the installation, as illustrated here.

It is worth noting that I have created these screenshots myself, in VirtualBox, from material downloaded safely from archive.org! It seems that Microsoft has published the necessary files as public domain over there.1,2,3

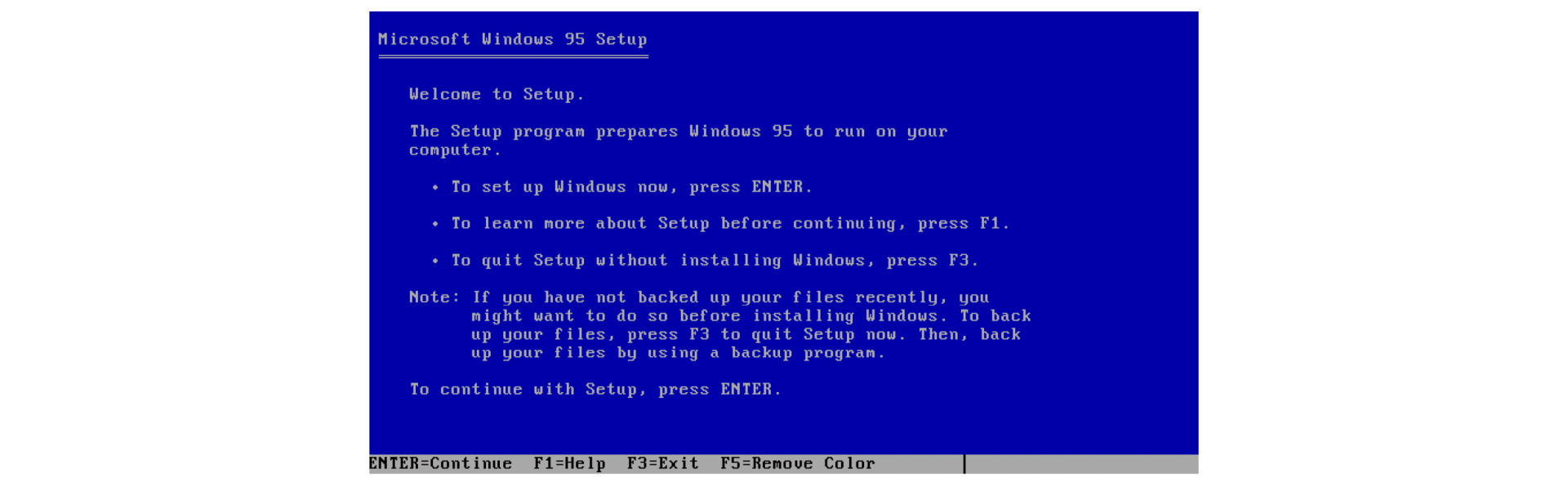

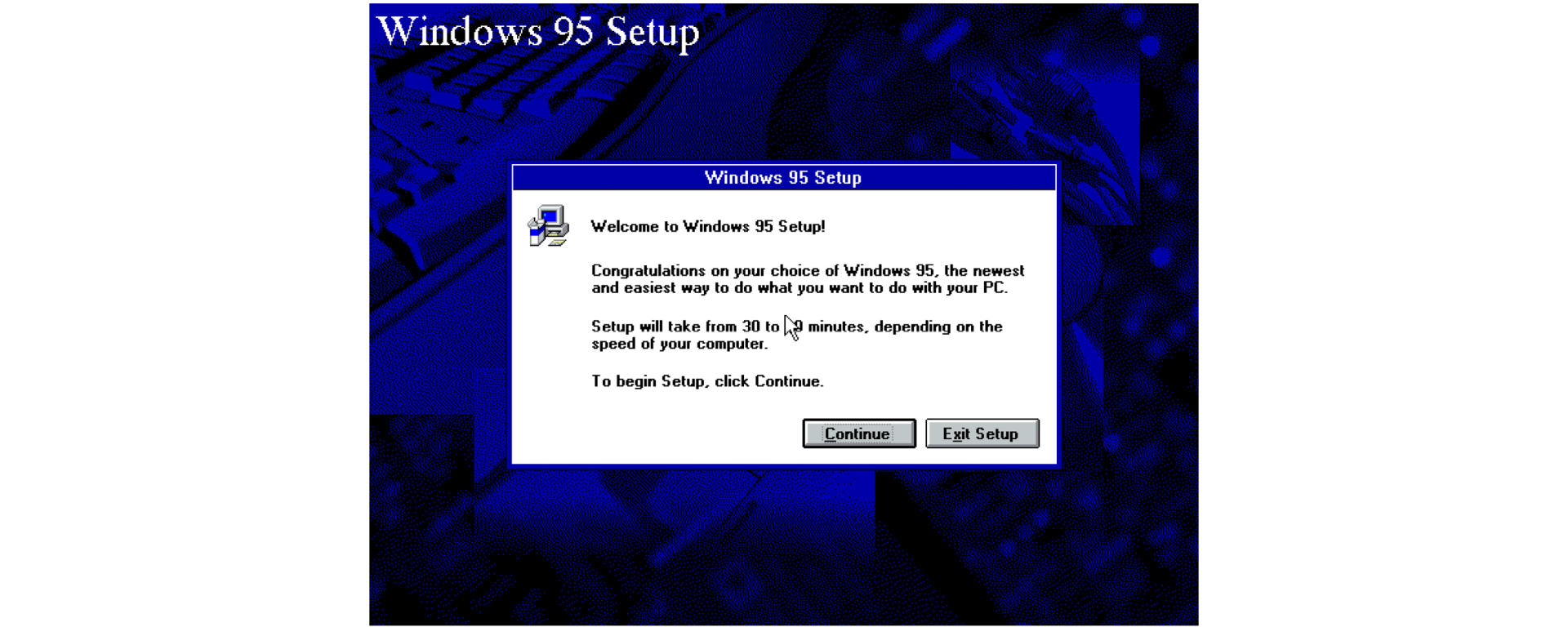

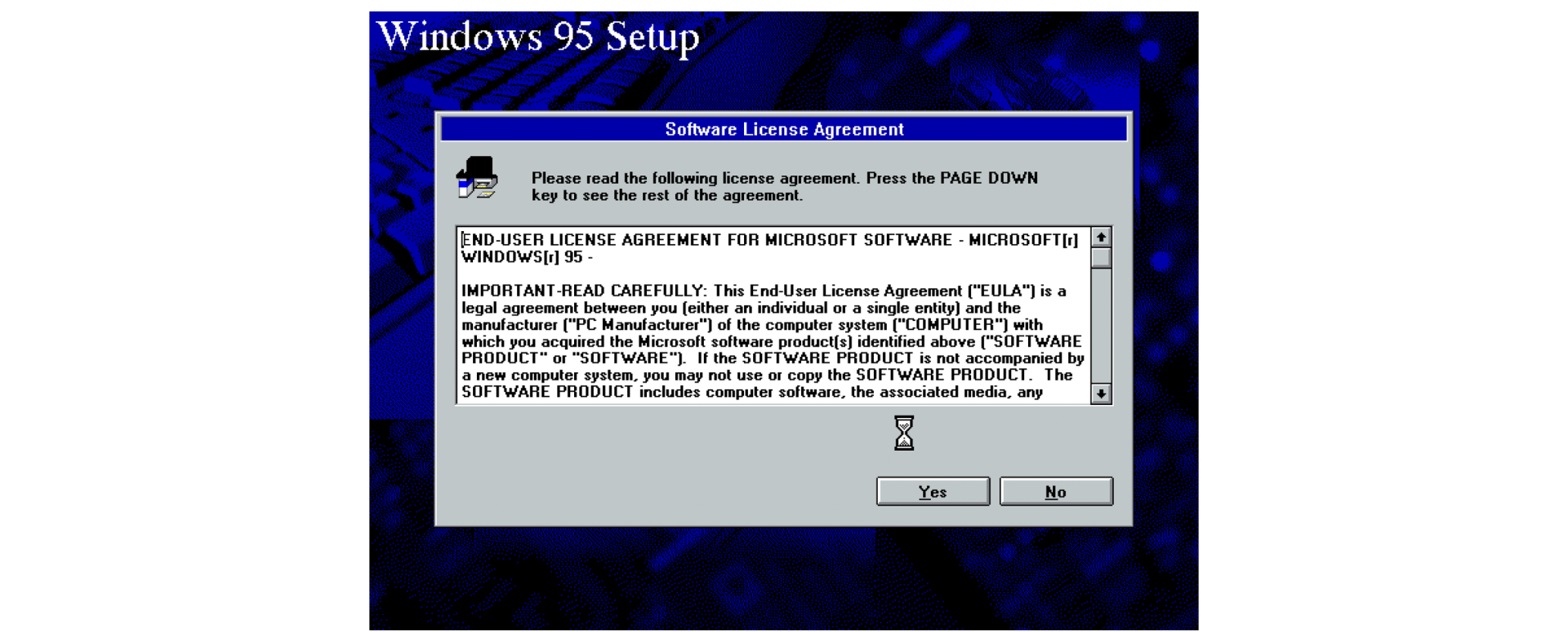

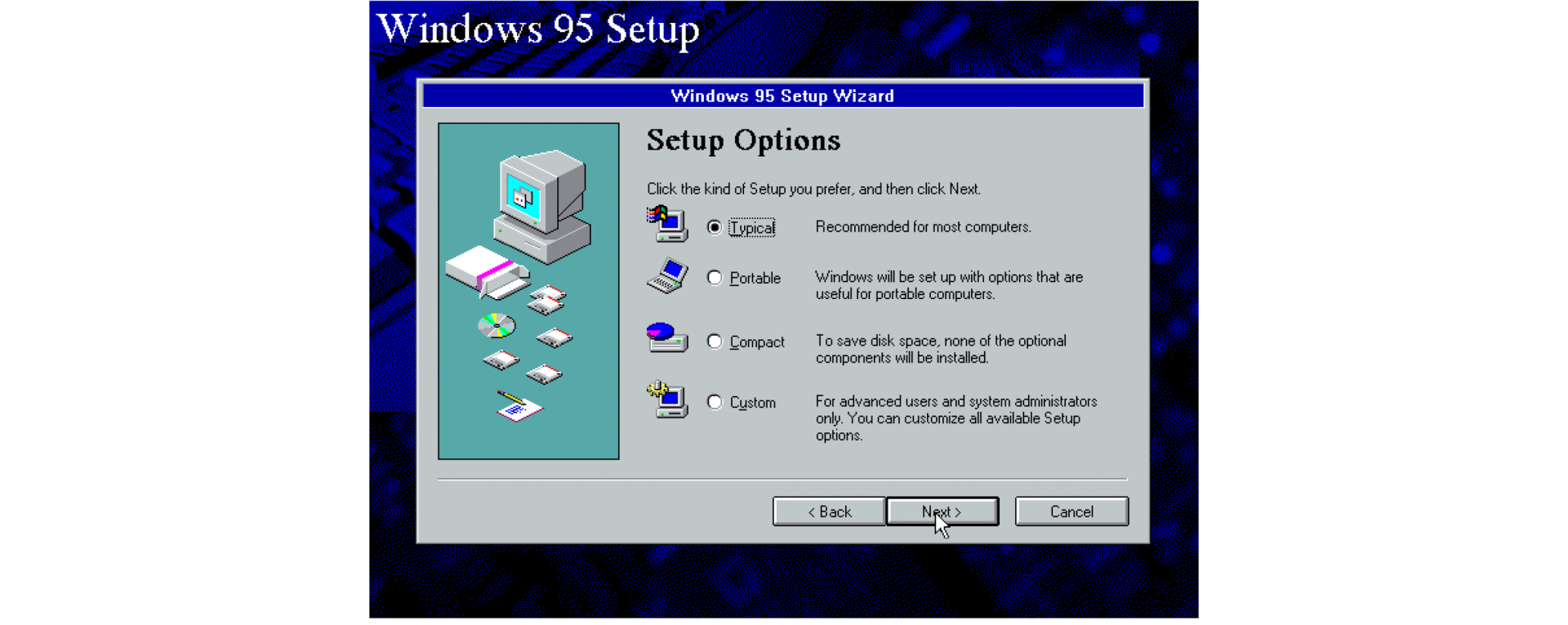

Going forward brings us to Windows 95. Just like Windows 3.11, it leveraged its own user interface in the installer, albeit with two intermediate steps. Here again, the screenshots tell a story, and it was relatively painless to install; the number of steps requiring user interaction was noticeably higher.4

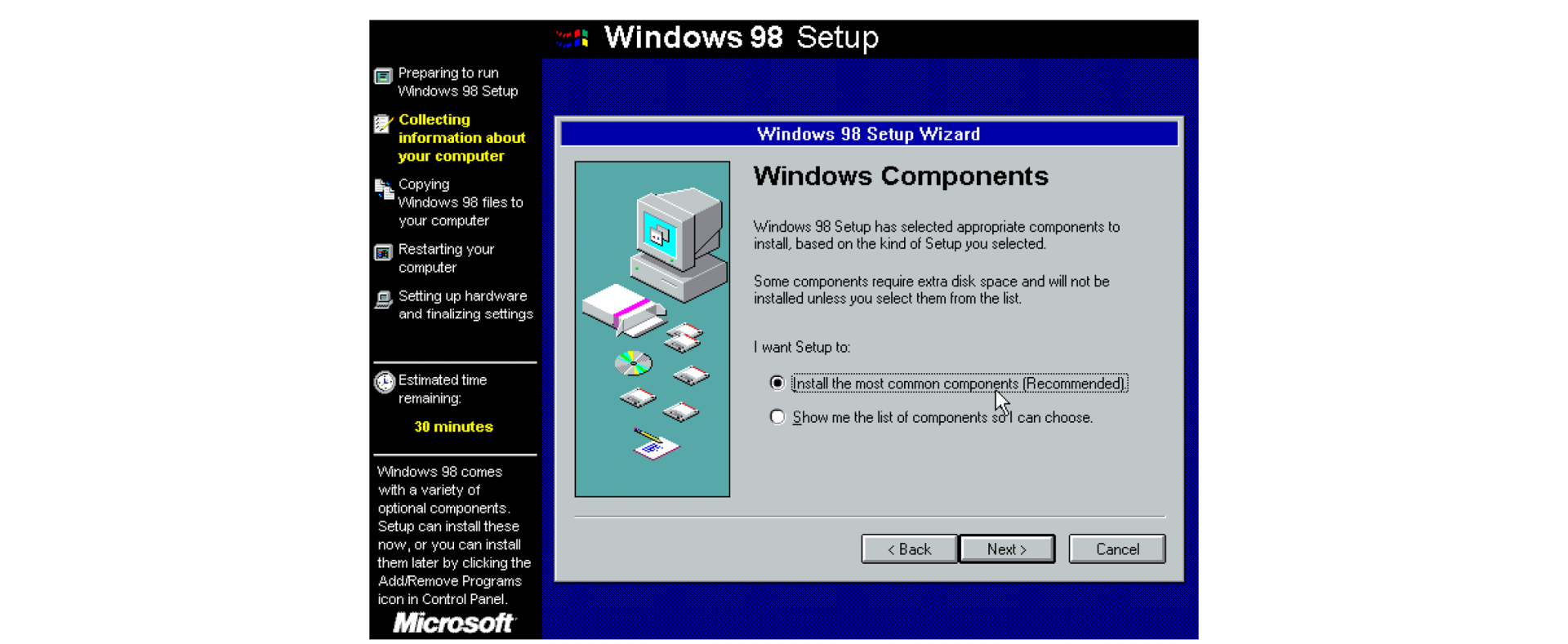

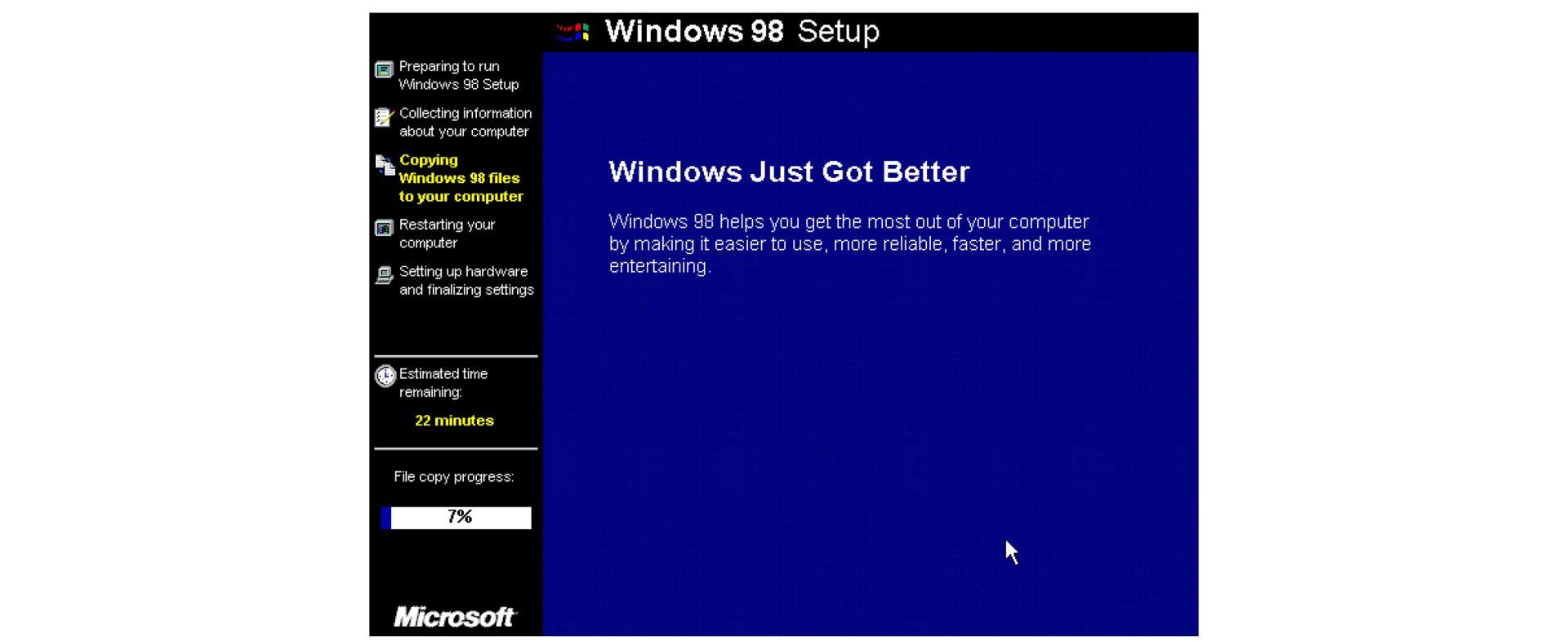

Including Windows 98 in this list is worth a mention, since it brought some improvements: a list of the overall steps, and a time estimate for the remaining process.5

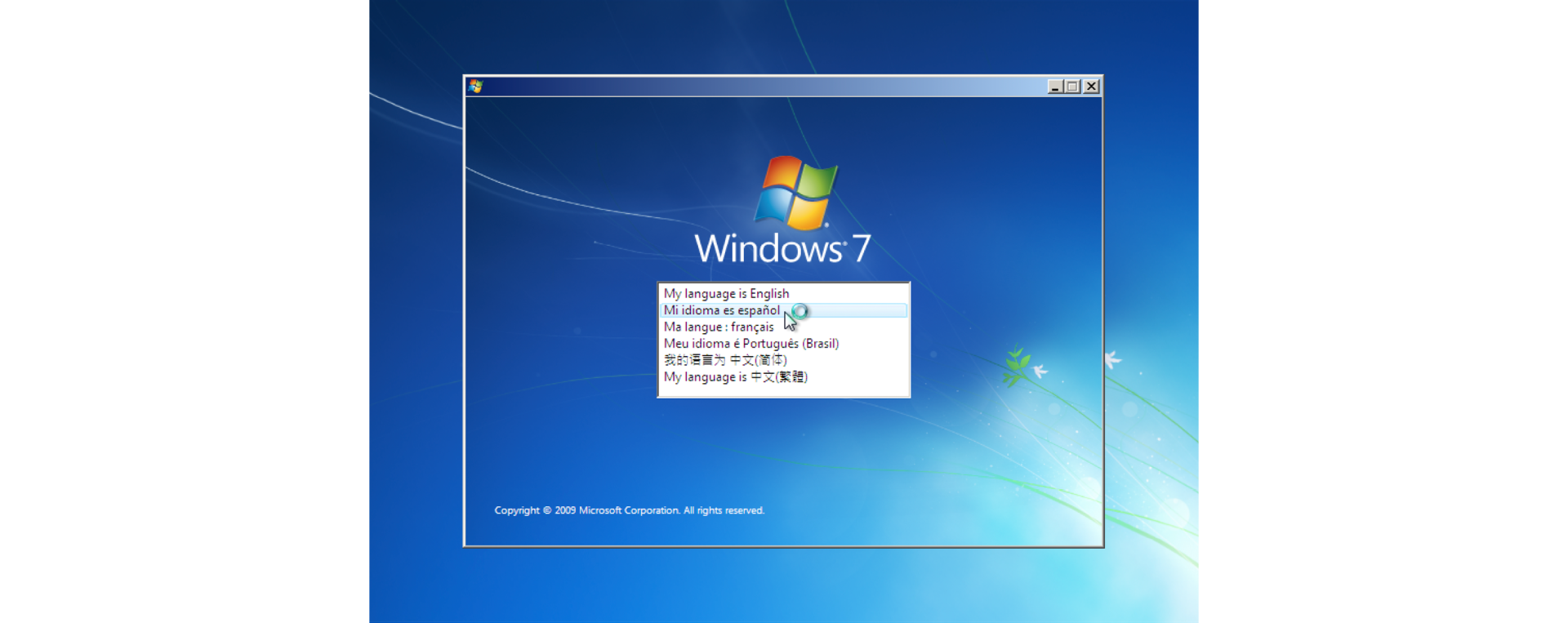

I will spare you the pain of going through the installation of every version of Windows. With the simple addition of Windows 7, we can already extract some patterns regarding the usability of its installer:6

We could endlessly argue whether FreeBSD actually competes with Microsoft Windows. From its own web homepage, the FreeBSD project does have the ambition to target desktop systems. This is now evidenced by the Laptop Desktop Working Group (LDWG). But without entering this debate, I think we can only benefit from looking at the consumer market, if only as a reference. The following patterns and criteria clearly emerged from this experience here:

|

Criteria |

MS-DOS 6.22 |

Windows 3.11 |

Windows 95 |

Windows 98 |

Windows 7 |

|

Language support |

MIX (different releases for each language) |

YES |

|||

|

Accessibility |

YES (high contrast) |

NO |

NO |

NO |

YES (magnifier, |

|

License agreement |

NO |

NO |

YES |

YES |

YES |

|

Number of steps |

9 (with 3 disks) |

15 (first 5 disks) |

21 |

17 |

10 |

|

Navigation |

NO |

NO |

YES |

YES |

NO |

|

Advanced mode |

NO |

MIX |

YES |

YES |

YES |

|

List of steps |

NO |

NO |

NO |

YES |

MIX |

|

Questions first |

NO |

NO |

NO |

NO |

NO |

|

Time estimate |

NO |

NO |

NO |

YES |

YES |

|

Live system |

NO |

NO |

NO |

NO |

NO |

|

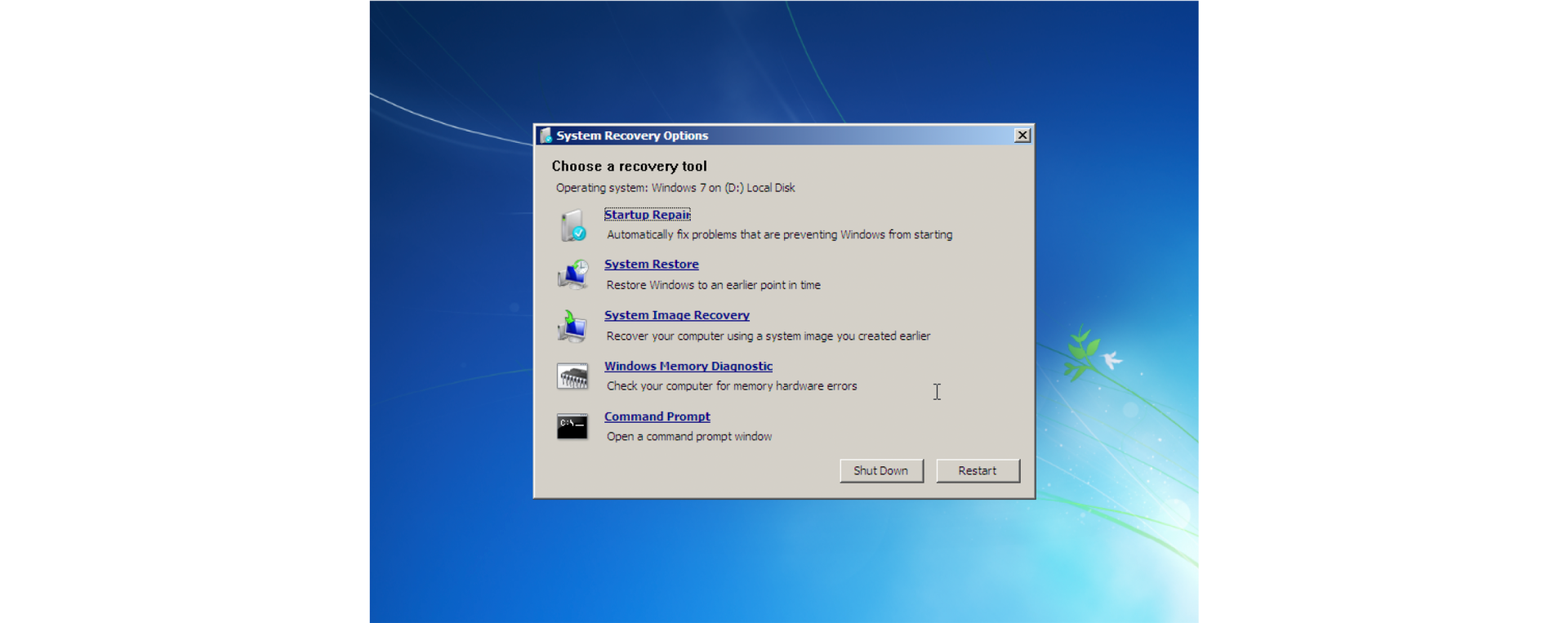

Repair system |

MIX |

MIX |

MIX |

MIX |

YES |

|

Text mode |

YES |

NO |

NO |

NO |

NO |

|

Graphical mode |

NO |

MIX |

MIX |

MIX |

YES |

|

Graphical outcome |

NO |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

|

Automation |

NO |

NO |

NO |

NO |

YES |

If I had to summarize the strength of this series of installers, I would point out:

- Indicators for overall progress were often provided.

- The time estimate, however inaccurate as it can be, can feel useful to the end user.

- Only the most essential decisions were left up to the user (target disk and installation directory), with the technical decisions left out by default:

- Choice of filesystem technology,

- List of drivers to install,

- Desktop environment, (evidently)

- Pre-installed list of applications. Alternatively, there was a clear way into an advanced mode.

- It was often possible to revert a decision and come back to the previous menu; curiously, Windows 7 dropped this possibility, but it was the most trivial version to install, with only 10 steps.

- The final system was directly usable for desktop use.

Although three major versions of Windows have been released since Windows 7, I am not aware of significant changes to the outcome in terms of usability.

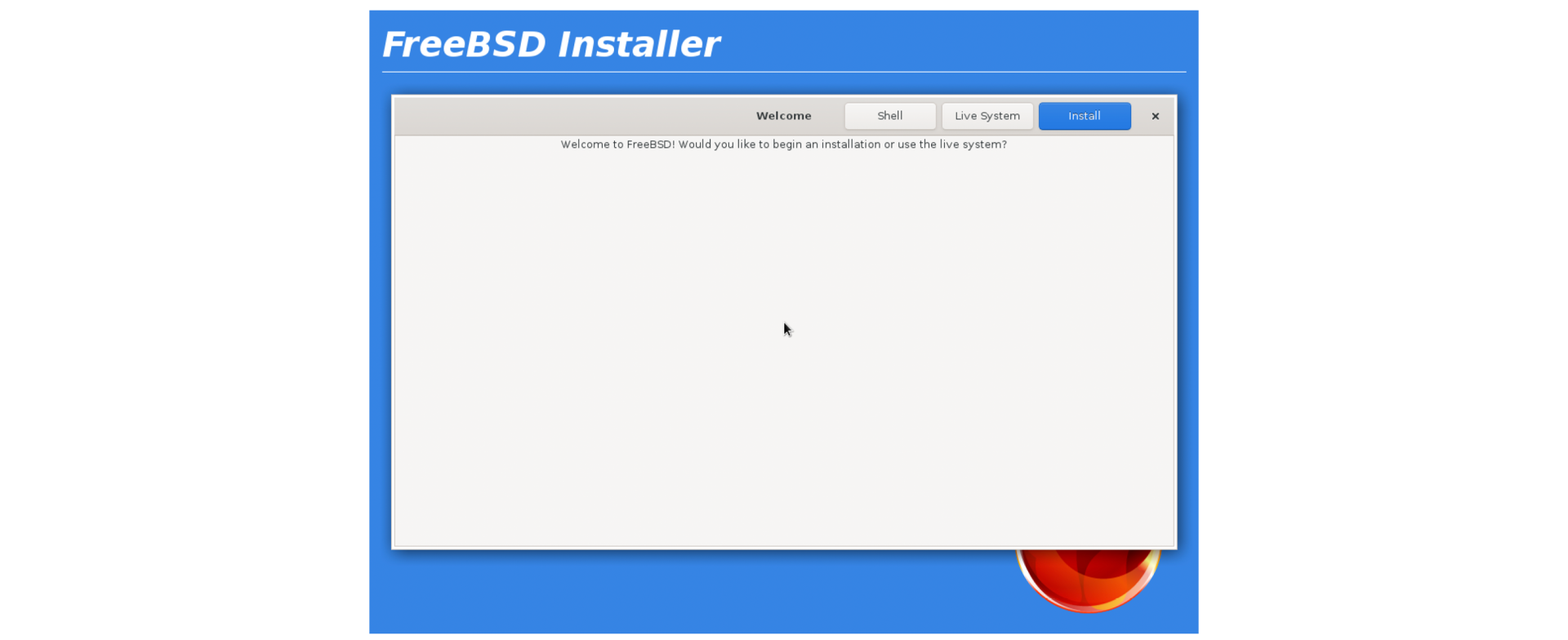

FreeBSD as of today

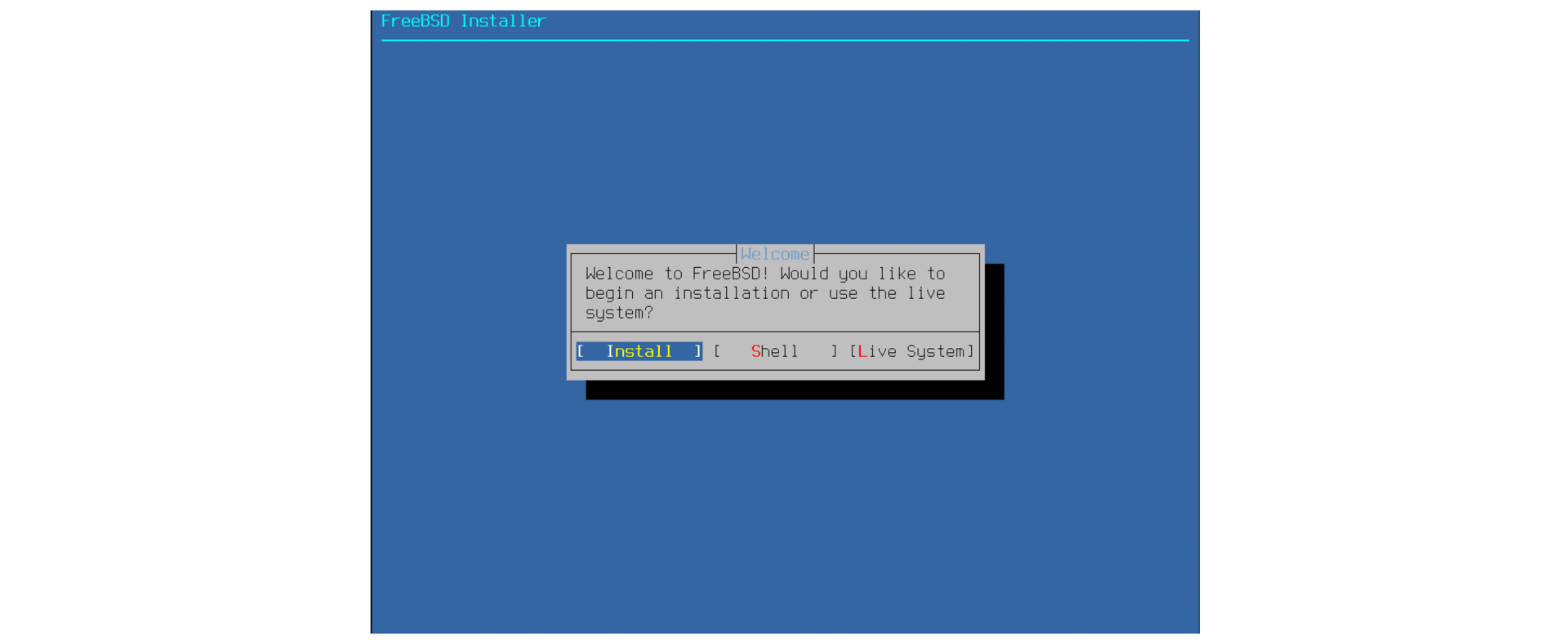

The latest release while writing these lines is version 14.2.7,8

After a fresh installation of Windows 7, if only looking at the usability aspect, the FreeBSD installer is certainly dated and left behind.

|

Criteria |

FreeBSD 14.2 |

|

Language support |

NO |

|

Accessibility |

NO |

|

License agreement |

NO |

|

Number of steps |

23 |

|

Navigation |

NO |

|

Questions first |

NO |

|

Advanced mode |

YES |

|

List of steps |

NO |

|

Time estimate |

NO |

|

Live system |

MIX (CLI) |

|

Repair system |

MIX (CLI) |

|

Text mode |

YES |

|

Graphical mode |

NO |

|

Graphical outcome |

NO |

|

Automation |

YES |

However, the comparison is not necessarily fair: Microsoft Windows clearly targets non-technical users, who are expecting a graphical interface, in a one-size-fits-all approach, and offers customer support.

So how does FreeBSD fare when facing its closer competition?

Linux Ubuntu (server)

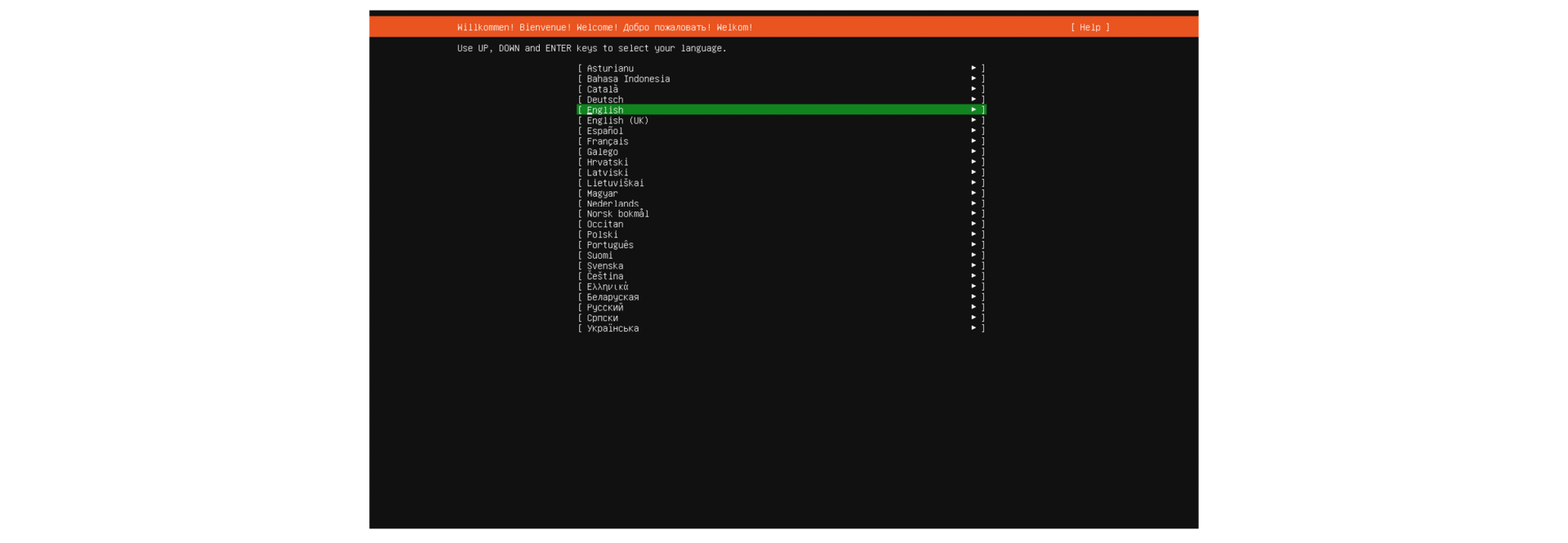

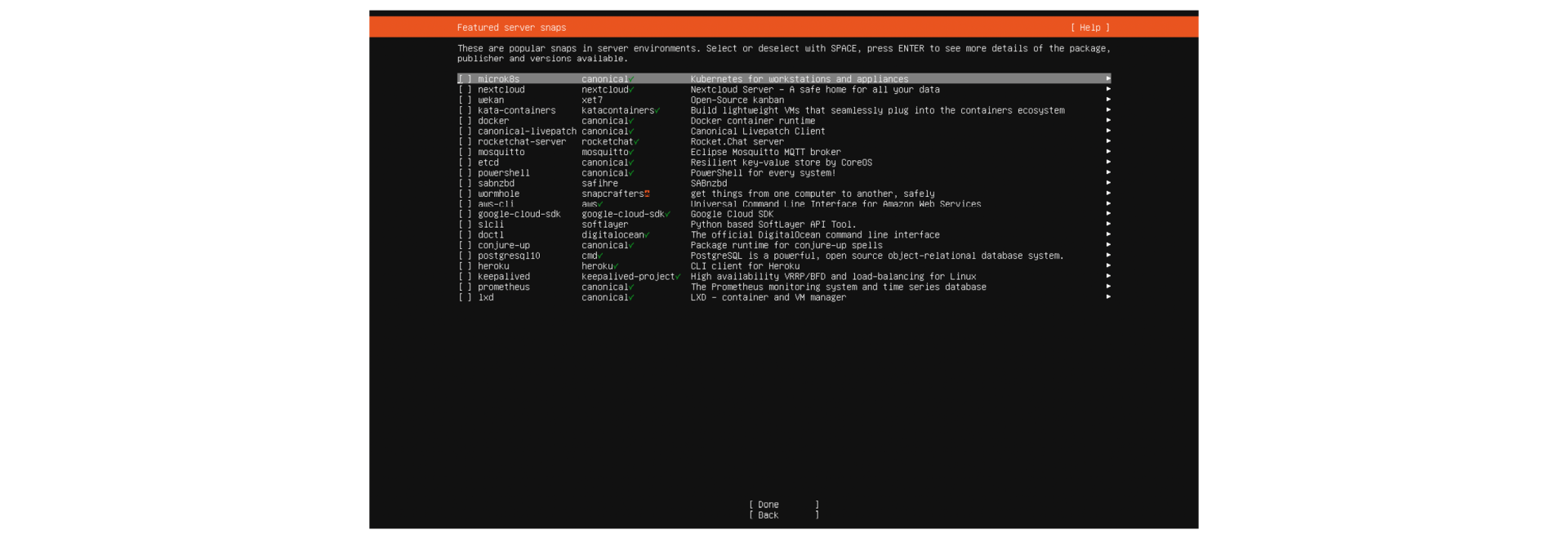

Ubuntu offers different installation images, depending on the purpose of the installation. I have used Ubuntu Server in its version 24.04.02 LTS for the initial comparison.9

Looking at this installer, at first glance it is much closer to what FreeBSD offers! The system is kept in text mode throughout the process, including the user login prompt concluding the first boot. This is certainly more on par with the FreeBSD installer. But other than that, the process felt simpler and more straightforward.

|

Criteria |

Ubuntu (server) |

|

Language support |

YES |

|

Accessibility |

NO |

|

License agreement |

NO |

|

Number of steps |

15 |

|

Navigation |

YES |

|

Questions first |

YES |

|

Advanced mode |

YES |

|

List of steps |

NO |

|

Time estimate |

NO |

|

Live system |

MIX (CLI) |

|

Repair system |

MIX (CLI) |

|

Text mode |

YES |

|

Graphical mode |

NO |

|

Graphical outcome |

NO |

|

Automation |

YES |

Definitely a closer match to FreeBSD’s own offering. I would identify the following aspects as key improvements over FreeBSD however:

- Support for multiple languages in the installer.

- Questions asked in a batch, the actual installation performed in one go.

- Installation purposes available during the installation (snaps).

Linux Ubuntu (desktop)

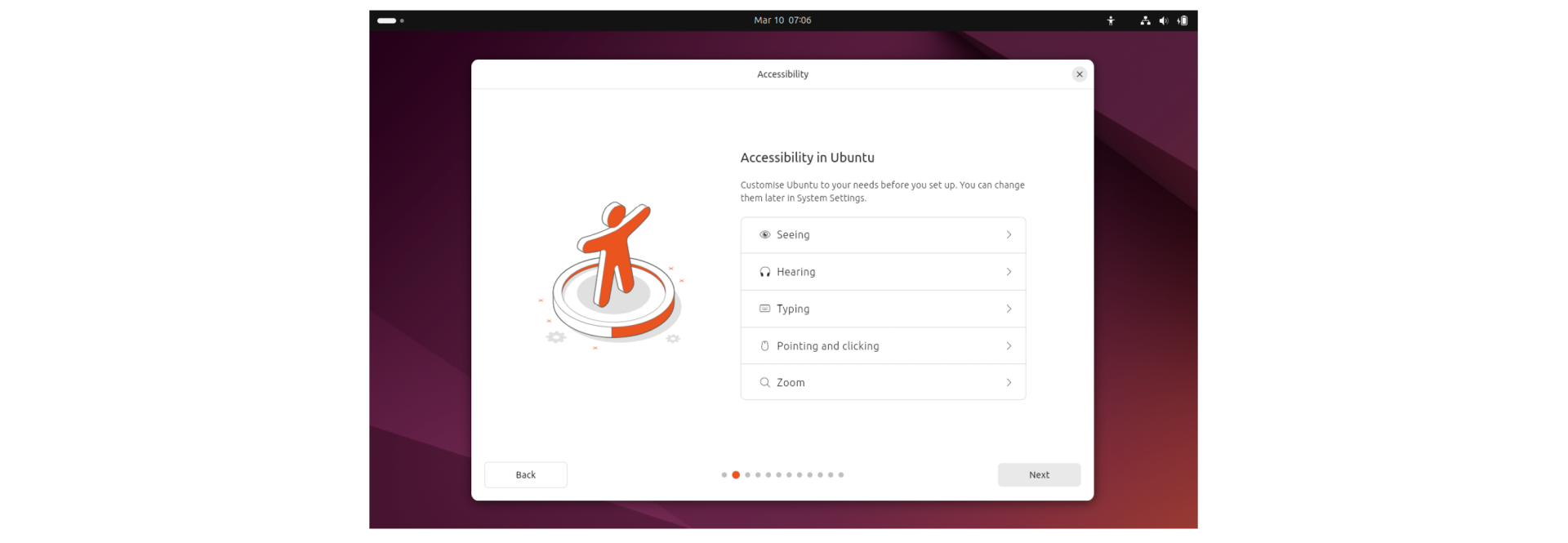

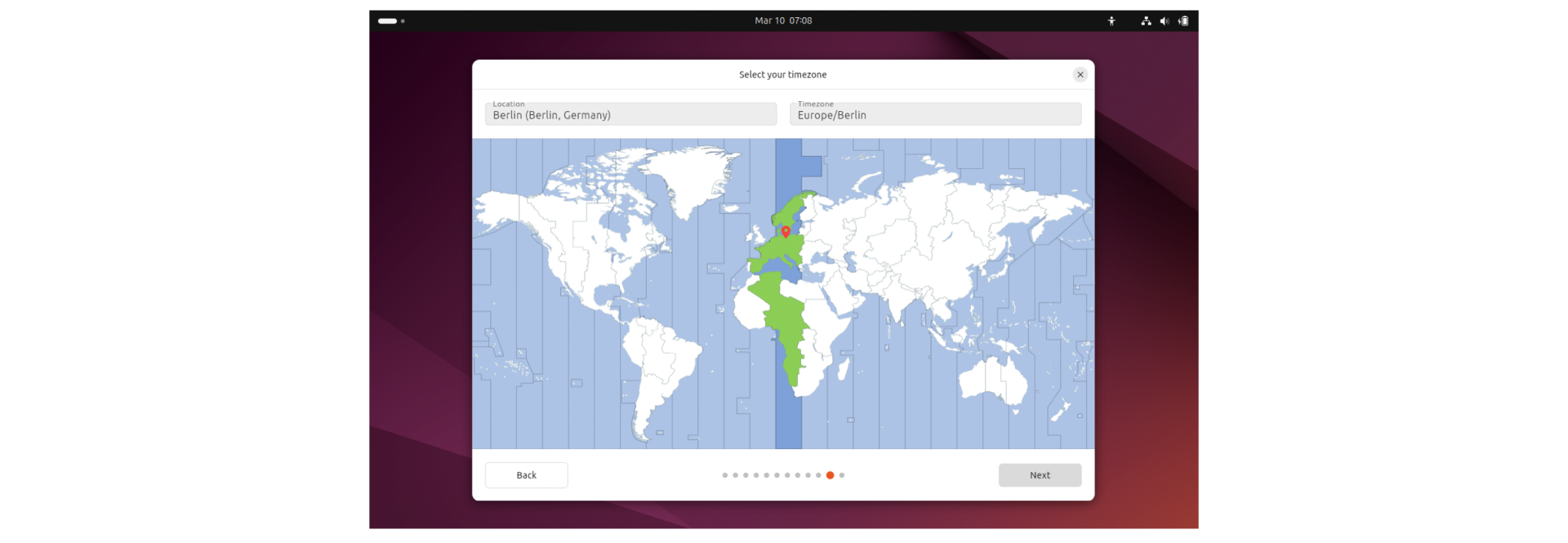

Next, I have tried Ubuntu Desktop, also in version 24.04.02 LTS.10

As expected, this version provides a graphical user experience. But more than that, the overall level of quality and polishing was — in my own perception anyway — on a different level.

|

Criteria |

Ubuntu (desktop) |

|

Language support |

YES |

|

Accessibility |

YES |

|

License agreement |

NO |

|

Number of steps |

15 |

|

Navigation |

YES |

|

Questions first |

YES |

|

Advanced mode |

YES |

|

List of steps |

NO |

|

Time estimate |

NO |

|

Live system |

YES |

|

Repair system |

MIX |

|

Text mode |

NO |

|

Graphical mode |

YES |

|

Graphical outcome |

YES |

|

Automation |

YES |

In terms of usability, this is definitely a reference. As for Microsoft Windows, this can be expected from a solution with commercial support. But it would be more fair to compare FreeBSD to another community project. For this reason, before diving deeper into FreeBSD’s own installer, let’s see if we can learn from Ubuntu’s parent, non-commercial distribution: Debian.

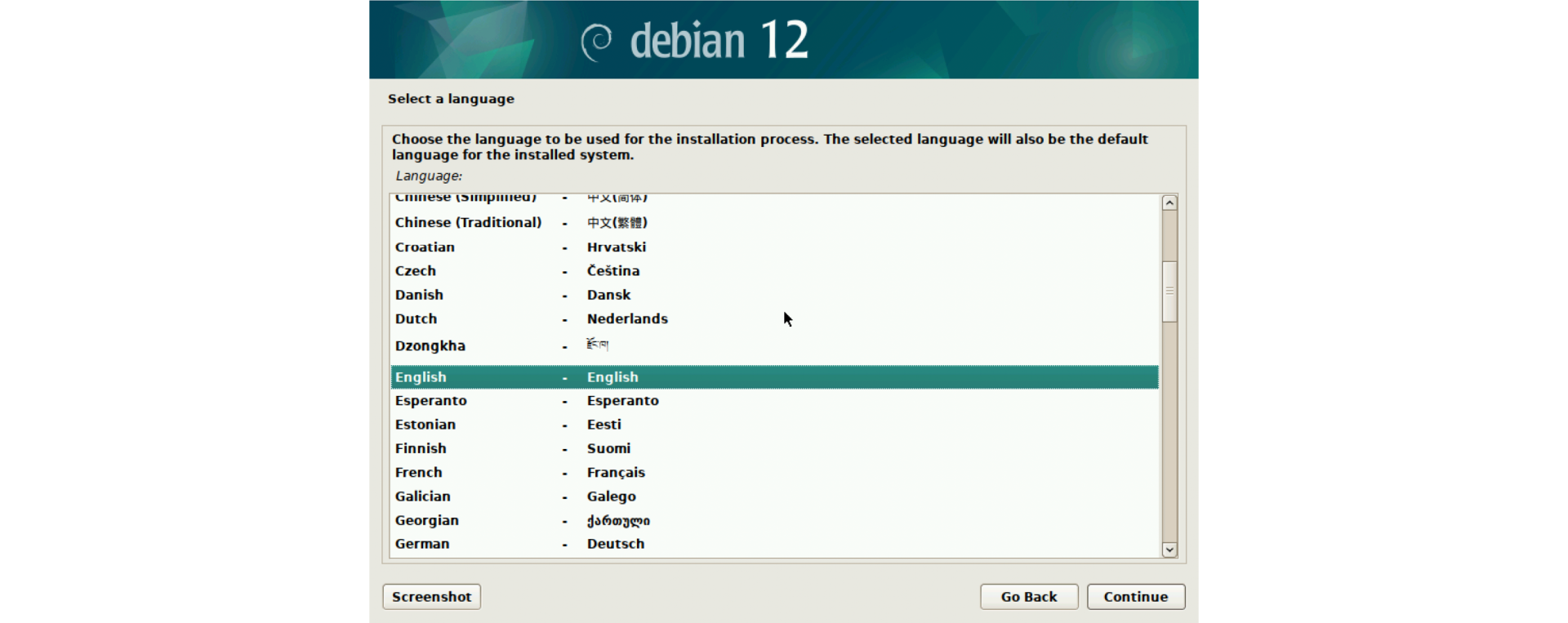

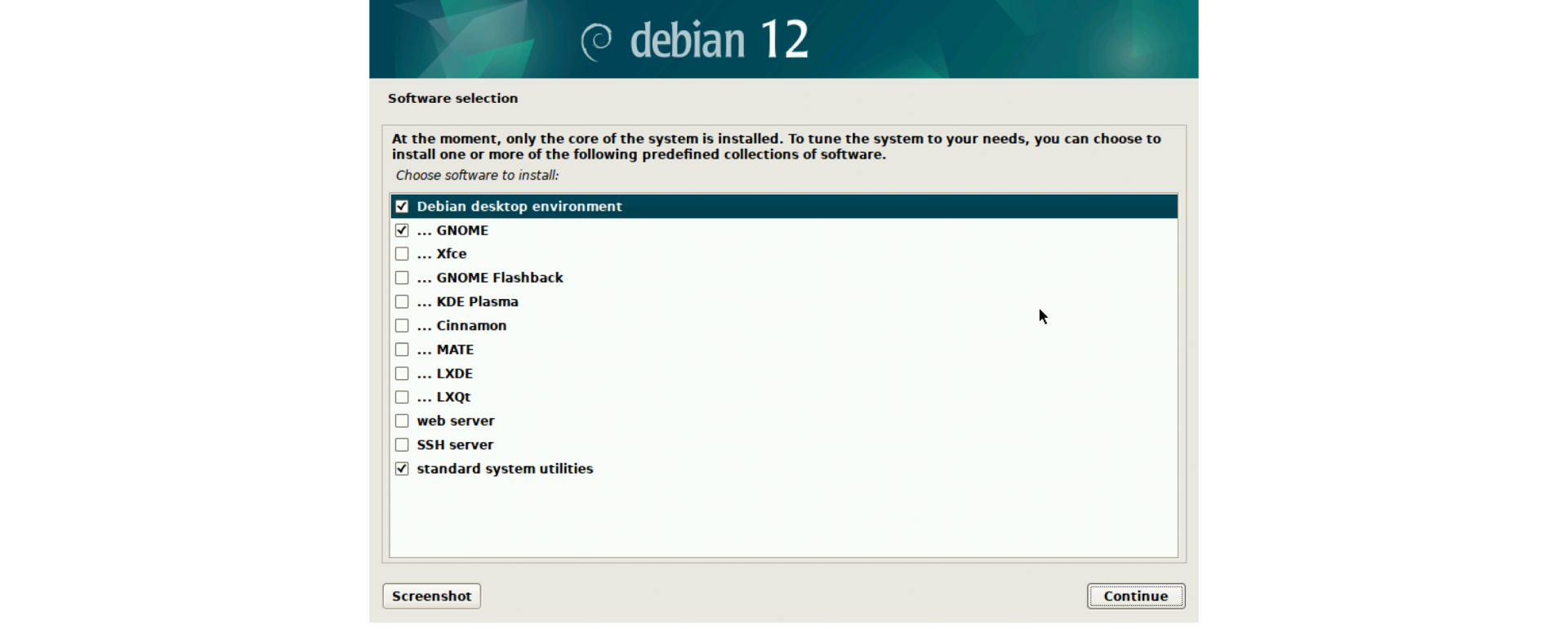

Debian GNU/Linux

Unlike Ubuntu, this last comparison will be a two-in-one: it turns out that the netinstall version of Debian’s installer, at only 632 MB, features both a text-based installer and its graphical equivalent.11

On another personal note: before switching mainly to BSD systems, my longtime UNIX-like distribution of choice was Debian. After the pleasant surprise of the hybrid approach, I ran into a frustrating repeat of this past experience: the installation process asks a seemingly endless list of questions, and a lot of time-consuming activity often takes place between each set.

|

Criteria |

Debian GNU/Linux |

|

Language support |

YES |

|

Accessibility |

NO |

|

License agreement |

NO |

|

Number of steps |

26 |

|

Navigation |

MIX |

|

Questions first |

NO |

|

Advanced mode |

NO |

|

List of steps |

NO |

|

Time estimate |

MIX |

|

Live system |

YES (other image) |

|

Repair system |

MIX (CLI) |

|

Text mode |

YES |

|

Graphical mode |

YES |

|

Graphical outcome |

YES |

|

Automation |

YES |

In spite of offering a graphical mode, the visual appearance was rather crude. I was also surprised to not find an accessibility mode beyond the high contrast mode in the boot menu; I suspect I may have simply missed it.

On a very positive note however, it was very easy to obtain an installation suitable for either server or desktop use. This matches perfectly with the hybrid approach for the installer.

Can FreeBSD achieve a similar outcome?

Special mention: macOS

Last but not least, I would like to mention macOS. While also originally based on a BSD system, macOS can rely on a database of well-known, in-house hardware targets. The system firmware is shipped with a number of fallback mechanisms in order to (re-)install the system in different ways, including without installation media: the whole system can be pulled from the Internet by the firmware.

This is impressive, and on par with the commercial offerings above; but again, this is unfair to our beloved FreeBSD system. However, I would like to insist on the availability of enough basic tools to allow for analysis and repair operations; this can be a life-saver in unexpected situations.

Diving into FreeBSD

From my own experience looking at its source code, the current situation with FreeBSD’s installer is a direct consequence of some design decisions. I would like to emphasise that this is not pure criticism of its implementation, or of the decisions made at the time; the point is to understand where we are, if the installer is ripe for a rewrite, or if some battles can be fought (and won!) with easy steps.

Architecture

Most of the FreeBSD installer is written as a combination of shell scripts, with a few steps implemented as dedicated C programs. The entire source code can be found in the src.git repository, but under the hood, it really consists of three main components:

- bsdconfig, under usr.sbin/bsdconfig, which is used as a library of shell routines by bsdinstall and its set of scripts.

- bsddialog, under usr.bin/bsddialog, is the tool interacting with the user, both for obtaining input and for monitoring the activity.

- Finally, bsdinstall itself is under usr.sbin/bsdinstall.

When starting the FreeBSD installation image, a dedicated rc.local startup script (from release/rc.local) concludes the boot process by running startbsdinstall. This script offers the welcome screen, as well as the possibility to use the installation media as a live system. By default, the live mode simply spawns a shell, which is known territory for regular UNIX users, but does not really qualify as a live or repair system for the average user.

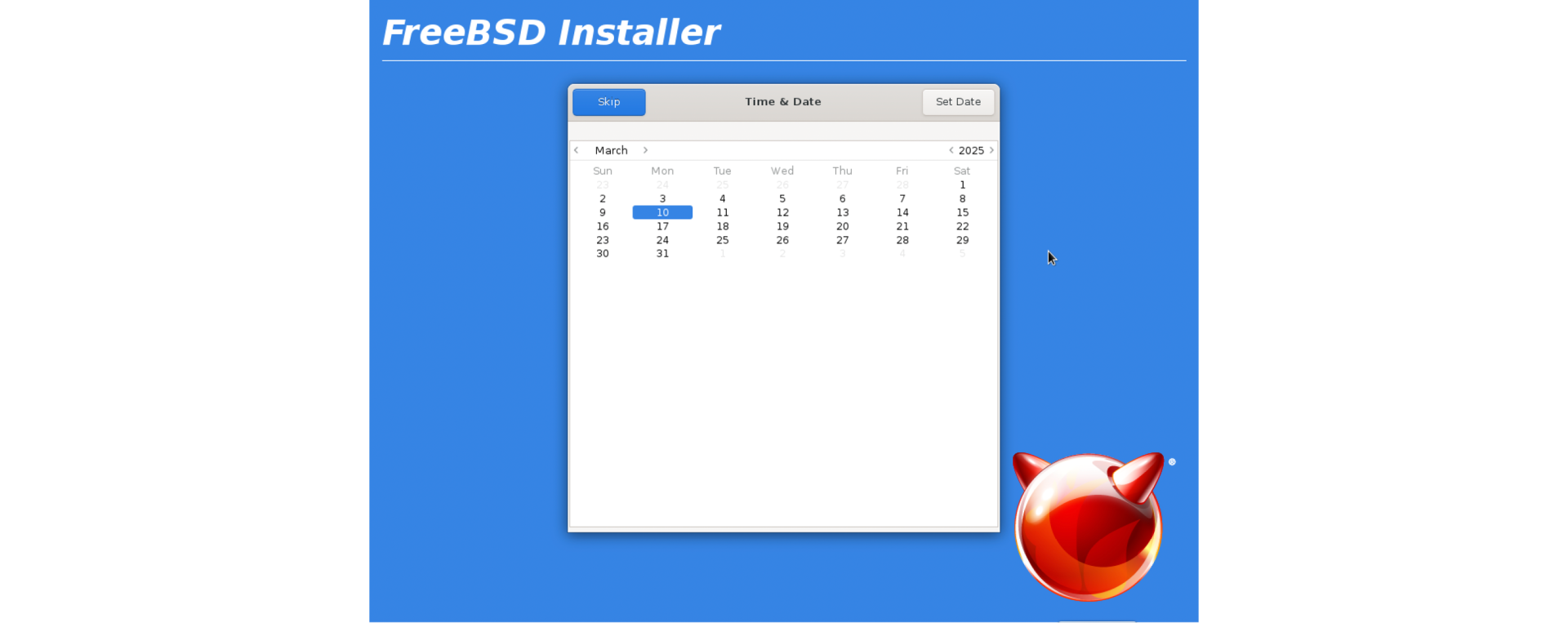

If we focus on the installation process, the procedure is performed as follows:

- startbsdinstall (see above).

- bsdinstall can be called directly with a specific operation, as found in

/usr/libexec/bsdinstall, and defaults to auto (our choice here). - auto performs a series of operations:

- Optionally, local.pre-everything if present.

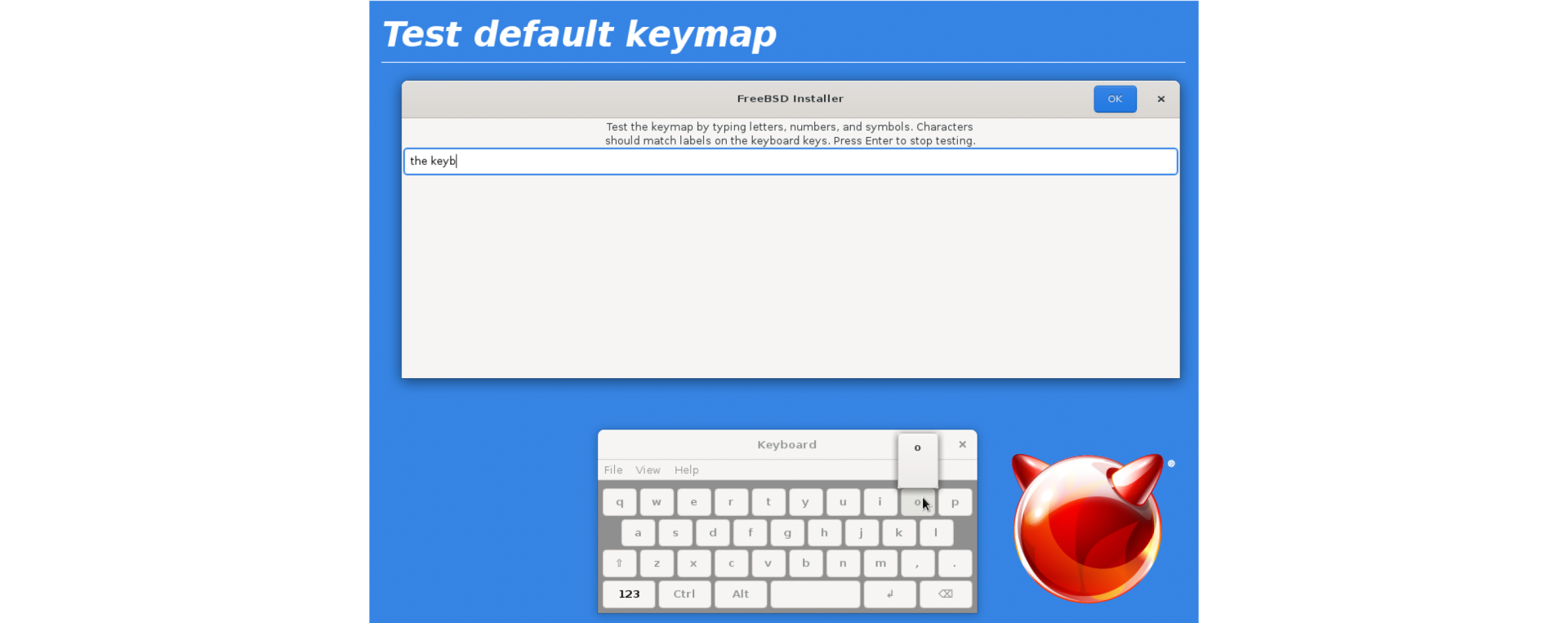

- keymap lists different possible keyboard layout.

- hostname sets the hostname for the target system.

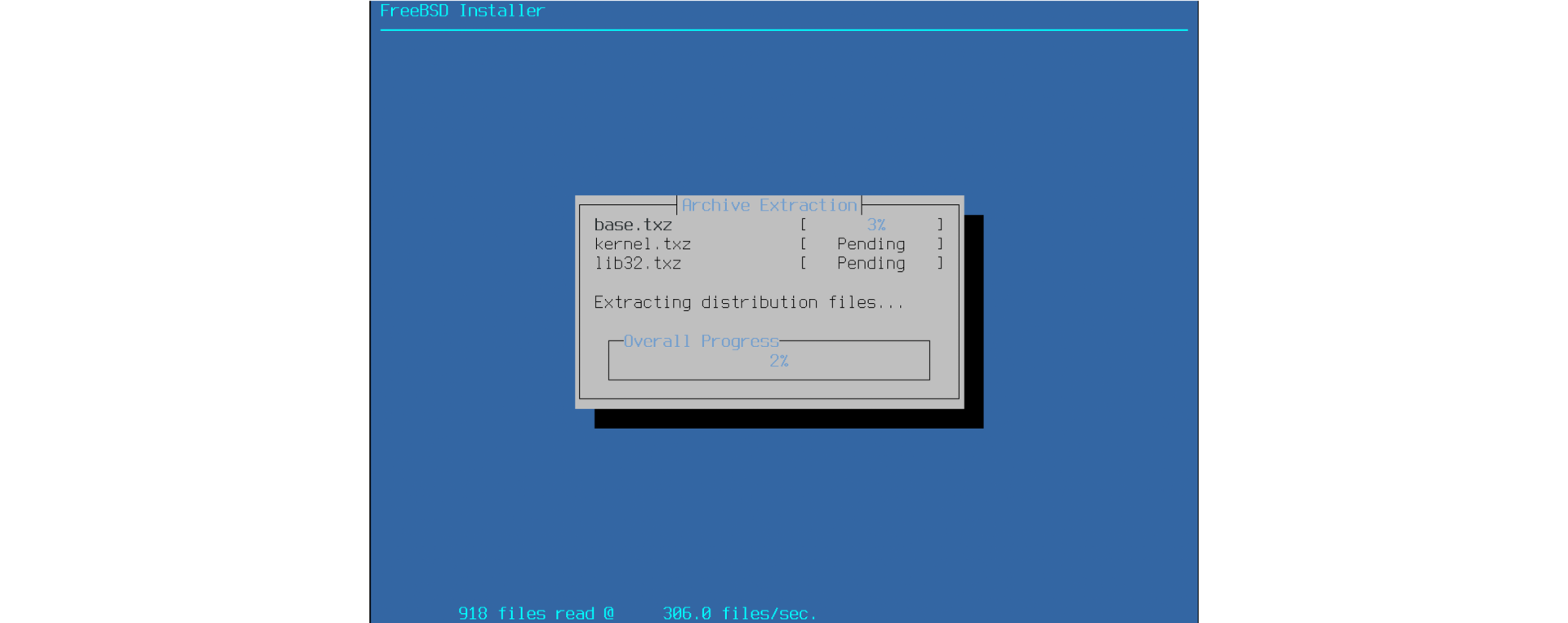

- Selection of optional system components, as per the MANIFEST file (which should be at least base.txz and kernel.txz).

If any system component is missing from the installation media:

- netconfig

- (Optionally, local.pre-partition if present).

- Application of known quirks depending on the platform detected (e.g., via SMBIOS or boot architecture).

- Choice of partitioning scheme (UFS automated, manual setup, or ZFS if supported).

- Application of the partitioning scheme and mounting of the target filesystem.

- (Optionally, local.pre-fetch if present).

- If any system component was found to be missing from the installation media:

- fetchmissingdists (saved within the target volume in /usr/freebsd-dist).

- checksum and distextract verify and extract the system components.

- bootconfig configures the bootloader.

- (Optionally, local.pre-configure if present).

- rootpass prompts for the root password.

- If the network hasn’t been setup yet, netconfig configures the network.

- A series of questions:

- time sets the date, time, and timezone.

- services offers a selection of services to be started at boot.

- hardening offers some hardening measures to be applied.

- firmware allows the installation of firmware packages.

- adduser allows adding user accounts, but calls adduser(8) with chroot(8) to do so, which surprisingly alters the look & feel of this operation.

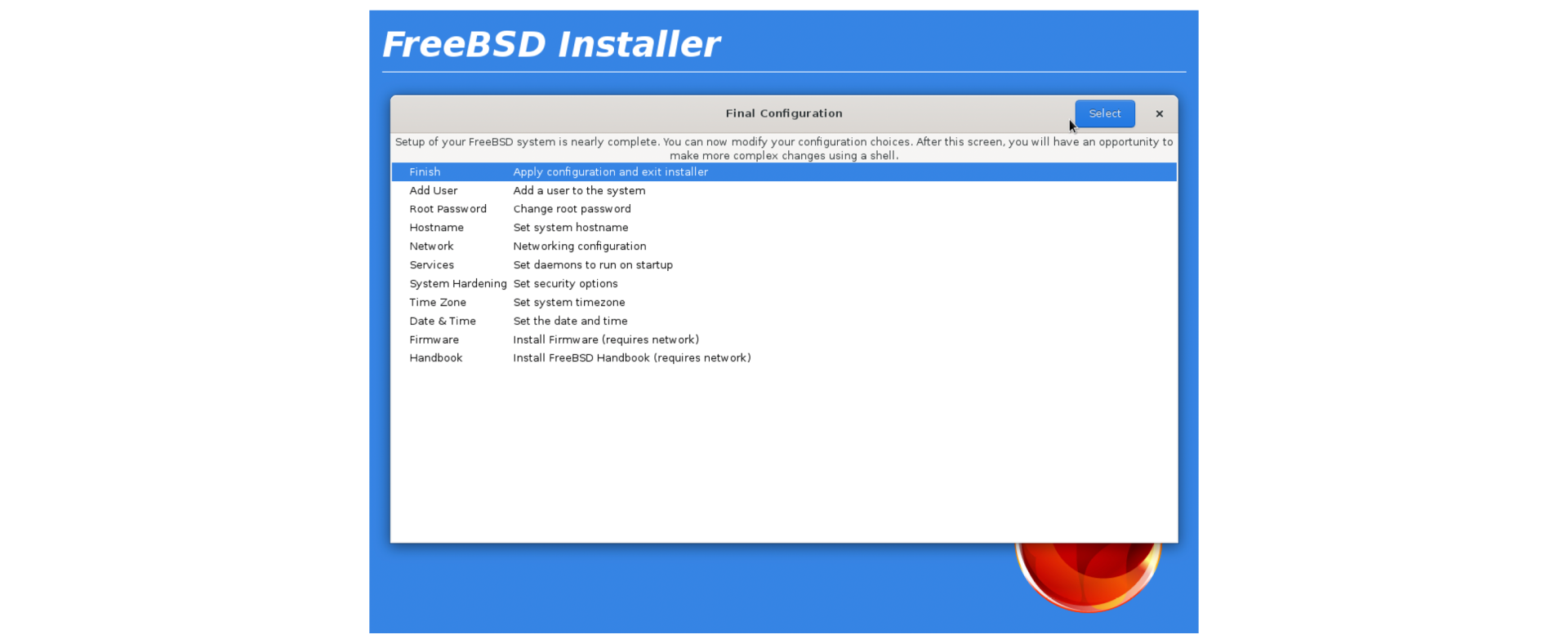

- A not-quite final menu, finalconfig, allows further changes before restarting.

- A non-interactive step, config, actually applies the configuration values chosen above.

- Cleanup of any system component downloaded.

- (Optionally, local.post-configure if present).

- One last final menu, lets the user start a shell within the target system (with chroot(8))

- A non-interactive security step saves entropy.

- Finally, umount allows for a safe reboot.

- Back to startbsdinstall, if bsdinstall(8) was successful the user is greeted with a comforting message, and offered to reboot or shutdown the system, or to spawn a shell.

As a first, positive note, we can see that the installation process behaves well even when missing the installation files for the system components. This allows installation media to be generated in different sizes, without having to modify the installation logic.

On another hand, this is an awful lot of questions for the user. They may feel essential and useful in isolation, but most of the systems described above deliver functional systems with a third of the interactive steps. Unfortunately, this is not the only problem identified with the user interface.

Limitations and use cases

Heavy reliance on bsddialog(1) (or libbsddialog for the C programs) introduces limitations similar to those of e.g., the Debian installer: the user interface for each step is rather basic, and does not support dynamic interaction according to the user input. As an example, the network configuration step will not be able to suggest a suitable network mask, DNS server or gateway, according to the most common conventions. This could not only save some keystrokes and unnecessary efforts for the user, but would also feel more modern and polished overall.

Possible solution: Lua This specific aspect could be solved with the introduction of Lua scripting capability in libbsddialog or otherwise in bsddialog(1). This has been suggested by the author of bsddialog, Alfonso Siciliano (asiciliano@), who is currently considering implementing this extension into the project.

Beginner users An easy win for beginners, or generally for desktop users, would be the possibility to conveniently install a desktop system, ready and functional upon the first reboot. While introducing an additional step, it could be inspired by the Debian installer (as illustrated above) and fit both server and desktop use.

There is ongoing experimentation in this direction (notably by Alfonso) but this is easier written in an article, than implemented reliably. Some of the challenges involve the installation of the corresponding firmware files, drivers, including a particular pain point with the DRM kernel modules. There is an ongoing effort (hi manu@ and thanks!) to move the latter from the ports back into the base system, which should help with recurring version mis-match issues in the current binary ports.

Enterprise use On a positive note this time, the FreeBSD installer can be tweaked and automated for deployment typical of enterprise use.

First, it is capable by default to set up jails instead of performing regular installations. This behaviour can be selected with the jail target, instead of the default auto described above. The operation then looks as follows:

# bsdinstall jail /path/to/the/new/jail

Should the FreeBSD installer be re-implemented or modified extensively, it might be important to keep this functionality in mind. On the other hand, numerous jail management solutions already exist outside of bsdinstall(8).

More importantly, the installer also supports a script target, which then requires an installation script to be executed in the context of bsdinstall. This has to be provided by the system administrator but allows for fully automated installations with the FreeBSD installer.

I have to wrap up this section with a missing feature, observed in all of the competition above, and documented in Bugzilla’s #214390: the installer assumes no proxy is necessary to reach the Internet. In my own experience penetration-testing deployment environments, on premise at dozens of different customers, this limitation was usually disqualifying.

Development environment

To be fair, it can be rather difficult to work on the implementation of bsdinstall(8). Testing some changes often requires building a full bootable image, running it into a virtual environment, and repeating installation steps until reaching the corresponding situation. In order to be more efficient when working on the installer, I have experimented with a development environment suitable for this purpose.

It consists of a PXE-based setup, which can be tweaked for traditional PXE environments as well as more modern, UEFI-assisted network boots. I had to combine this boot sequence with a TFTP server (managed by inetd), a DHCP service (with the isc-dhcp44-server package), and a read-only NFS mount. Describing the entire setup goes beyond the scope of this article, but the usability of the FreeBSD installer depends on that of its development environment after all. Feel free to adapt the following snippets to your own taste.

For /etc/exports:

/jail/bsdinstall -ro -network 192.168.x.0 -mask 255.255.255.0 -maproot 0:0

For /etc/inetd.conf:

tftp dgram udp wait root /usr/libexec/tftpd tftpd -l -s /tftpboot

tftp dgram udp6 wait root /usr/libexec/tftpd tftpd -l -s /tftpboot

For /etc/rc.conf:

mountd_enable=”YES”

nfs_server_enable=”YES”

nfs_server_flags=”-h 192.168.x.y”

rpcbind_enable=”YES”

rpcbind_flags=”-h 192.168.x.y”

For /usr/local/etc/dhcpd.conf:

option subnet-mask 255.255.255.0;

default-lease-time 600;

max-lease-time 7200;

subnet 192.168.x.0 netmask 255.255.255.0 {

range 192.168.x.128 192.168.x.254;

option routers 192.168.x.y;

option subnet-mask 255.255.255.0;

}

option arch code 93 = unsigned integer 16;

host example {

hardware ethernet aa:bb:cc:dd:ee:ff;

fixed-address 192.168.x.127;

next-server 192.168.x.y;

if option arch = 0:07 {

#UEFI

filename “FreeBSD/boot/loader.efi”;

} else {

#BIOS

filename “FreeBSD/boot/pxeboot”;

}

option root-path “192.168.x.y:/jail/bsdinstall/”;

}

The files loader.efi and pxeboot should be placed in the /tftpboot/FreeBSD/boot folder.

You may want to setup this /jail/bsdinstall folder as a typical jail, tweaking it to reflect the regular boot environment of the installer, or to expose the disc1 folder from a release build instead. Either way, this should save you from generating, transferring, or rebooting image files when working on bsdinstall.

Note that this setup works equally well for physical hardware and as Virtual Machines, since hypervisors like VirtualBox support booting from PXE.

Graphical mode

Finally, it is time to answer the question: can we improve the FreeBSD installer, and bring it to feature parity with that of Debian for instance?

Background

In early 2024, I was tasked by the FreeBSD Foundation to look at the state of the art of graphical installers in the Open Source landscape. The underlying goal was to identify a possible approach for the FreeBSD project to add this feature. Calamares12, a new installer framework for Linux, was an obvious candidate — if it could be confirmed to be usable with FreeBSD as the target system. Unfortunately, its use of the GPL license was found to be incompatible with FreeBSD’s target demographics of the base system.

Another alternative specific to FreeBSD, and with a lot of visibility at the time, was PC-BSD. After going through a first rebranding as TrueOS, it was discontinued in 2020. The alternatives suggested included GhostBSD, MidnightBSD, and NomadBSD.

GhostBSD features a graphical installer, gbi. While a good candidate, it would significantly differ from the current codebase of bsdinstall, while also requiring a complete Python and Gtk+ environment. It seemed to me that a more efficient approach was possible.

Neither MidnightBSD nor NomadBSD offer a graphical installer from what I could tell.

Least intrusive approach

Instead, being already familiar with bsdinstall and bsddialog, I could picture a way to re-use the existing code base and architecture, while performing the installation process with a graphical interface. By replacing bsddialog(1) with an equivalent tool, also BSD-licensed, it was possible to deliver a fully functional installation image within the few weeks assigned for the project.

Being already familiar with Gtk+, I considered it a reasonable trade-off if only to come up with a working demonstrator. Gtk+ is available under the LGPL license, which is still not enough a match for the target demographics. But I managed to implement gbsddialog, a desktop application equivalent to bsddialog, within a few days.

My initial vision for this tool was slightly different. I was hoping to apply additional workarounds or improvements:

- Prevent the dialog window from disappearing and reappearing each time between calls, for instance by leveraging the GtkPlug and GtkSocket widget.

- Using the GtkAssistant widget for a better look & feel, once the previous item addressed.

- A specific widget from bsddialog is implemented in a way that does not suit a graphical implementation of the tool: mixedgauge. In bsdinstall, the persistence of the console output of bsddialog is abused in order to give the illusion of progress, while in reality a new instance of bsddialog is executed for each update. In the graphical installer, this monitoring had to be replaced with a regular gauge widget, at the expense of usability.

On the other hand, I am quite happy with the implementation of the desktop window, reproducing the look & feel of the original bsddialog tool quite accurately in its graphical version. This part of the code is not very elegant as of now, but it does the job.

Repair and upgrade capability

I had the pleasure to co-mentor a Google Summer of Code project last year (hi Li-Wen!) with a very proactive student: Leaf Yen. The project was about bringing new capabilities to the FreeBSD installer: upgrading or repairing existing systems, with removable media.

The project concluded successfully, and was submitted as three pull-up requests on GitHub:

- #1395, GSoC 2024 — Improving Installer with Repair and Upgrade Ability.

- #1424, bsdinstall: Add pkg install support in live env.

- #1427, bsdinstall: Add repair scripts to installer menu.

I have not managed to integrate this work into the graphical version of the installer, but I consider it an equally important part of a modern installer. Consider this article a call for attention on this project too, which should be able to work equally well with the current installer and the graphical version once polished and merged.

Graphical installer as web application

This article would not be complete without this possible added bonus. Since Gtk+ 3, it is possible to render Gtk+ applications inside a web browser instead of a computer screen. This is implemented by the GDK Broadway backend.

While I haven’t experimented with this capability yet, it seems possible to turn the graphical version of the installer into a web server. This would allow the installation of FreeBSD systems over the network, without any additional change! This is clearly another potential easy win.

Accessibility

I would like to mention an additional criterion for the adoption of Gtk+ for the graphical installer demonstrator: accessibility.

While I am subject to my own set of impairments myself, they are not severe enough for me to have experimented much with Gtk+’ set of accessibility features. However, I was aware of its capabilities in this regard, and they are also relevant to the usability of an Operating System installer for the part of the population affected. In fact, I have heard of requests for accessibility support in the installer, either privately or at conferences.

There is even a funded project aiming at bringing accessibility features to the FreeBSD installer, under investigation by Alfonso Siciliano. (Hello again!)

Back to Gtk+, it supports the following requirements for accessibility:

- Screen readers, like Orca for conversion to speech or braille.

- Full keyboard navigation.

- Accessible behaviour in the standard widgets.

- Theming for high contrast or further visibility improvements.

- Text and interface scaling.

- Plug-in system for further improvements.

I have not had the opportunity to try out these features with someone affected, but I have kept this aspect in mind throughout the development of gbsddialog, sticking to the core Gtk+ API everywhere. As a result, the tool is compatible with both Gtk+ 2 and Gtk+ 3.

Before concluding this article, I am going to mention the DeforaOS desktop environment. It is another lightweight desktop environment, written by a single individual for the most part (hi!) and to be honest, it shows. It is nowhere near the level of completion and quality that I am aiming for. It is partly packaged in FreeBSD’s ports (thanks Olivier!) and I have used it as part of the demonstrator for the graphical installer here — if only to illustrate the capabilities.

Still, I am glad to mention that it features a virtual keyboard program, and that I could successfully deploy it in combination with the graphical version of the installer.

This allows me to update FreeBSD’s feature table as follows, considering the progress documented in this article:

|

Criteria |

FreeBSD 14.2 |

|

Language support |

NO |

|

Accessibility |

YES (magnifier, on-screen keyboard, high contrast) |

|

License agreement |

NO |

|

Number of steps |

22 |

|

Navigation |

NO |

|

Questions first |

NO |

|

Advanced mode |

YES |

|

List of steps |

NO |

|

Time estimate |

NO |

|

Live system |

YES |

|

Repair system |

YES |

|

Text mode |

YES |

|

Graphical mode |

YES |

|

Graphical outcome |

MIX (ongoing) |

|

Automation |

YES |

Conclusion

This can be a very divisive and subjective subject to tackle. I hope that this article will be helpful, so that the installation process can be improved for the next releases of FreeBSD. Unfortunately, working on the current code base is not always easy, and can require a lot of patience when it involves generating and booting installation media for each and every test. Simple changes can really harm hardware support or the overall quality of the user experience in unintended ways.

Evidently, there is ample room for improvement, and during my work on the installer, I have heard calls for a complete rewrite. It is not an easy decision to make, nor an easy project to implement — especially while addressing every possible use case, trying to please everyone, and keeping it within an adequate budget.

Quite frankly I do not feel like I am in a position to judge or impose a specific decision over another. I had hoped to be able to offer and maintain a simple evolution of the current installer myself, extending its current capabilities without bringing unnecessary changes. By reusing its code as described here, bugs fixed and improvements made to the console-based installer are reflected in the graphical version, and vice versa.

References

- https://archive.org/details/MS_DOS_6.22_MICROSOFT

- https://archive.org/details/windows-for-workgroups

- https://forums.virtualbox.org/viewtopic.php?t=102121

- https://archive.org/details/win-95-osr-2

- https://archive.org/details/windows-98-se-isofile

- https://archive.org/details/en_windows_7_professional_with_sp1_x64_dvd_u_676939_202302

- https://download.freebsd.org/releases/amd64/amd64/ISO-IMAGES/14.2/ (amd64)

- https://download.freebsd.org/releases/arm64/aarch64/ISO-IMAGES/14.2/ (aarch64)

- https://ubuntu.com/download/server

- https://ubuntu.com/download/desktop

- https://cdimage.debian.org/debian-cd/current/amd64/iso-cd/ (amd64)

- https://calamares.io