Universal Flash Storage on FreeBSD

Universal Flash Storage on FreeBSD

Universal Flash Storage (UFS) is a high-performance, low-power storage interface designed for mobile, automotive, and embedded environments. Today, UFS is widely deployed and has become the successor to eMMC in most Android flagship smartphones. It also appears in some tablets, laptops, and automotive systems. Linux has supported UFS since around 2012, OpenBSD since 7.3, and Windows since Windows 10.

However, FreeBSD did not have a UFS driver. If we were to bring UFS’s proven maturity from other ecosystems into the FreeBSD storage stack, FreeBSD would become a viable choice in many mobile and embedded domains. The question “Why doesn’t FreeBSD have a UFS driver yet?” became my personal motivation, and this article describes the path I took to answer it.

Until last year, I had never used FreeBSD. Over the course of approximately six months, I studied FreeBSD, analyzed its codebase, and eventually implemented a UFS driver. I hope this case shows that even someone new to FreeBSD can develop a device driver with a systematic approach.

This article provides a brief introduction to UFS, explains its architecture, development process, and driver design, shares its current status and future plans, and finally presents a hands-on environment using QEMU, allowing readers to follow along.

Note: FreeBSD also has the traditional UFS (Unix File System). In this article, “UFS” means Universal Flash Storage, not the file system. The driver name in the codebase is ufshci(4).

Universal Flash Storage Overview

In mobile storage, low latency and low power are essential, and compatibility with existing systems is also important. Rather than inventing an entirely new standard, UFS combines existing standards to achieve these goals. As a result, it was quickly adopted by the market. It retained the benefits of low power and reliability from its component standards, albeit at the cost of somewhat greater implementation complexity.

At the interconnect layer, UFS uses MIPI M-PHY (a reliable, differential high-speed serial interface) together with MIPI UniPro (a link layer with strong power management). On top of that, the transport protocol layer uses UTP, and the application layer uses a SCSI command subset whose reliability and compatibility are already well proven.

Where UFS is used

UFS may feel unfamiliar, but you are likely already using it. Most Android flagship smartphones use UFS for internal storage. UFS is also used in some low-power tablets and ultralight laptops, as well as in automotive infotainment, where reliability is critical.

Many high-performance ARM application processors integrate a UFS host controller, and some low-power x86 platforms (e.g., Intel N100) support a UFS host controller as well. Nintendo’s recently released handheld console, Nintendo Switch 2, uses UFS for internal storage.

As UFS adoption continues to grow, adding native UFS support in FreeBSD broadens its applicability to mobile and embedded systems. Anticipating this demand, I started this project.

UFS Architecture

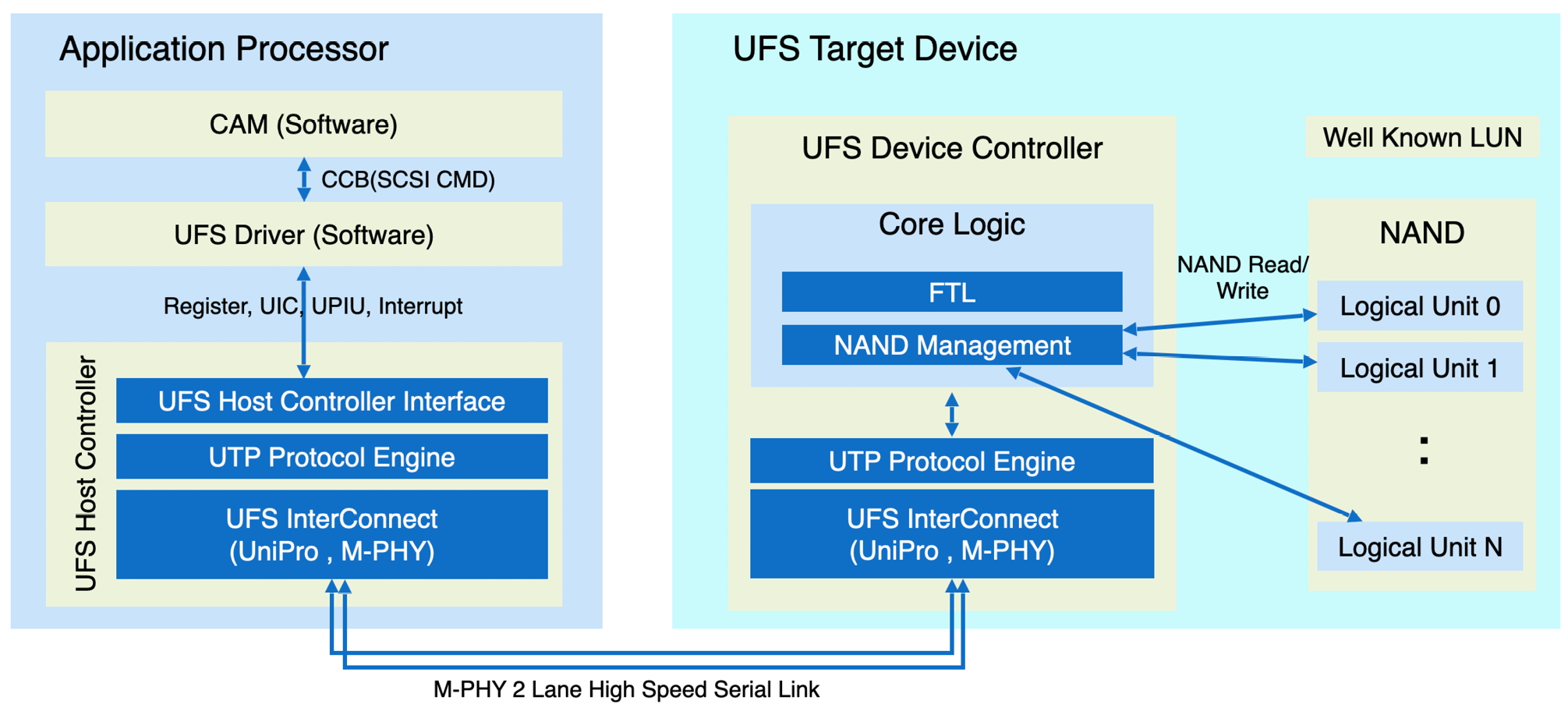

Figure 1. UFS System Model

A typical UFS system consists of a UFS target device (usually a BGA package on the PCB) and a UFS host controller integrated into the application processor SoC. The two components communicate over a high-speed serial link.

When an I/O request arrives, FreeBSD’s CAM (Common Access Method) subsystem builds a SCSI command in a CCB (CAM Control Block) and passes it to the driver. The driver encapsulates the SCSI command in a UPIU (UFS Protocol Information Unit) and enqueues it on the UFS host controller’s queue.

The host controller enqueues the request and rings the doorbell; data moves via DMA, and completions arrive via interrupts. The UFS device executes the SCSI subset command (e.g., READ/WRITE), accesses NAND flash, and returns completion or error status to the host controller.

In this way, the UFS device driver controls the host controller to perform reads and writes to the UFS device.

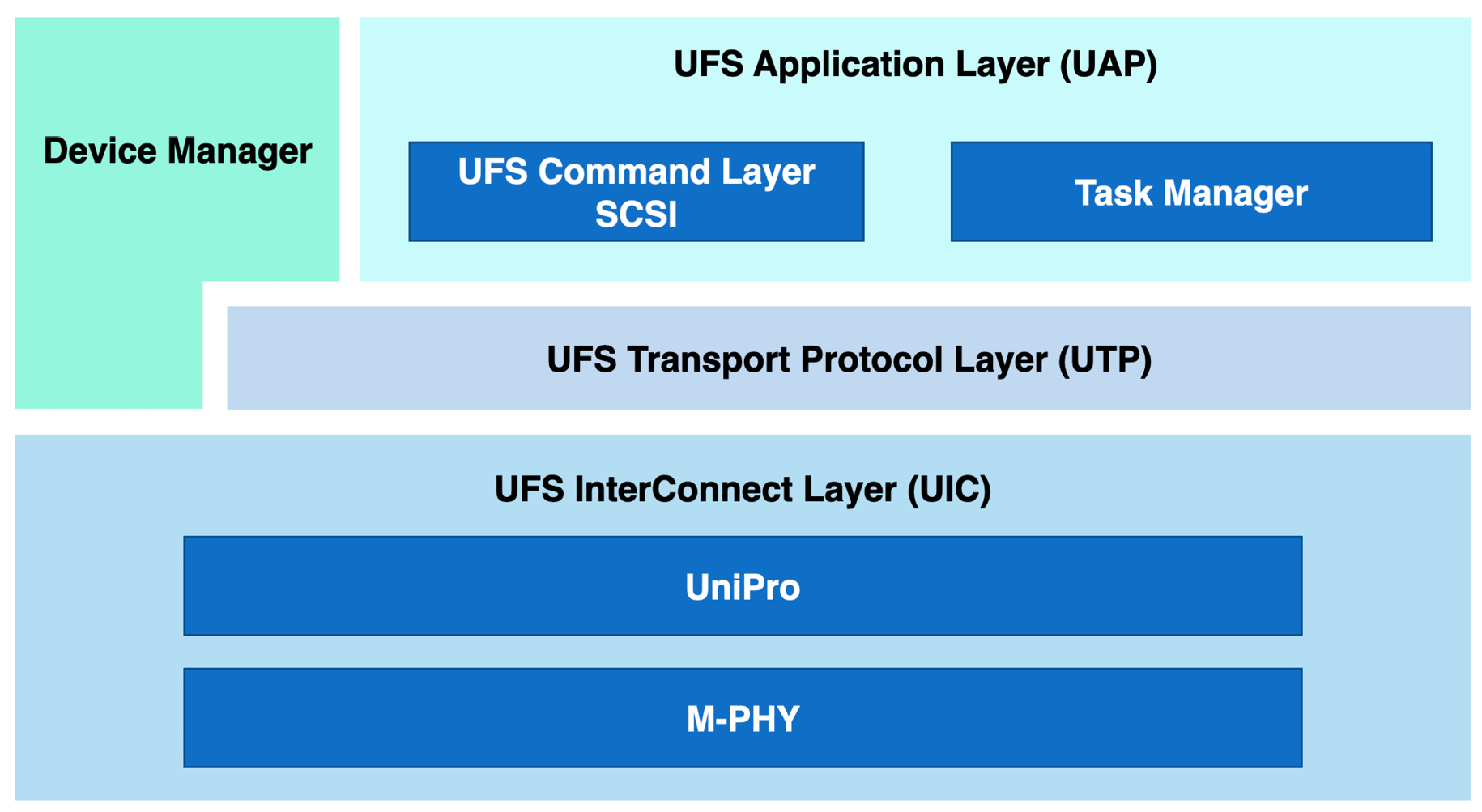

Figure 2. UFS Layered Architecture

As noted earlier, UFS layers several existing standards and is organized into three layers: interconnect, transport, and application. Their roles are:

- UIC (UFS InterConnect Layer): Manages the link. It performs Link Startup over M-PHY/UniPro, adjusts gear and lane settings to balance performance and power, supports power states (Active, Hibernate), detects errors, and performs recovery. The UFS driver controls this layer via registers and UIC commands.

- UTP (UFS Transport Protocol Layer): Transports admin and SCSI commands. The host controller maintains Admin and I/O queues; the driver enqueues requests and rings a doorbell. Data moves via DMA, and completions arrive via interrupts.

- UAP (UFS Application Layer): Handles commands (e.g., READ/WRITE) and command queue control. Although UFS defines multiple command sets, in practice, only the SCSI command subset is used. The UFS driver does not create SCSI commands; it encapsulates CAM-generated SCSI commands in UPIUs for UTP. This allows CAM’s standard paths for scanning, error handling, and retries to be reused as-is. Through this layer, CAM treats UFS as a standard SCSI device.

Key advantages (high performance, low power)

- Performance: Compared with eMMC’s half-duplex, parallel interface, UFS’s full-duplex, high-speed serial interface delivers higher bandwidth and lower latency. The submission path is lightweight, built around queues, DMA, and interrupts. As a result, performance is solid even with a single queue, and multi-circular queues (MCQ) improve scalability on multicore systems. WriteBooster further improves burst-write performance by using an SLC region of NAND.

- Power efficiency: The UIC link raises the gear only when I/O is active and quickly drops to a low-power state when idle. The standard defines power-state transitions, enabling longer battery life in thermal and power-constrained mobile form factors. In practice, tablets using UFS instead of NVMe have been reported to gain roughly 30-90 minutes of battery life.

- Compatibility: Because UFS uses a SCSI command subset, existing SCSI infrastructure can be reused. On FreeBSD, CAM handles SCSI processing, while the UFS driver encapsulates CAM-generated SCSI commands in UPIUs for UTP, making integration with CAM straightforward.

History and future of UFS

The UFS standard is published as JESD220 (UFS), and the host controller interface as JESD223 (UFSHCI). UFS/UFSHCI 1.0 was released in 2011. In 2015, UFS 2.1 devices first shipped in the Samsung Galaxy S6, marking the start of broad commercialization. UFS 3.0 improved link speed and introduced WriteBooster for burst writes. UFS 4.0 added multi-circular queues (MCQ), improving multicore scaling. UFS 4.1 is the current release, and UFS is deployed in most flagship smartphones.

As on-device AI workloads grow on smartphones and other mobile devices, UFS is evolving to enable the faster transfer of LLM models into DRAM. Because on-device LLM models must be loaded quickly, higher bandwidth is required; work toward UFS 5.0 targets higher link speeds by increasing the serial-bus clock rate to boost bandwidth.

Driver Overview

I proposed a UFS device driver on the freebsd-hackers mailing list in July 2024 and began analysis and design in January 2025. Fortunately, Warner Losh, now my mentor, replied and provided valuable guidance on the FreeBSD storage stack. The FreeBSD Handbook and BSD conference talks were also helpful. After about two months of analyzing CAM, SCSI, and the NVMe driver, I designed the UFS driver. Because NVMe and UFS share a similar structure, I reused many of the same ideas. I requested an early code review on May 16, 2025. After several review rounds, the work was committed on June 15, 2025, and included in FreeBSD 15.0.

Development was conducted primarily using QEMU’s UFS emulation, and was later validated on real hardware: Intel Lakefield and Alder Lake platforms with UFS 2.0/3.1/4.0 devices. I also aimed to test on ARM SoCs, but suitable hardware was difficult to obtain.

The UFS driver is tightly integrated with the CAM subsystem. During initialization, it registers with CAM; thereafter, SCSI commands for configuration and reads/writes are delivered from CAM to the driver. To maintain backward compatibility with UFS 3.0 and earlier, the driver supports both the single doorbell queue (SDQ) path and the multi-circular queue (MCQ) path.

Device initialization and registration

Initialization follows the UFS layered architecture, proceeding from the bottom layer upward.

- UFSHCI Registers: Enable the host controller, program required registers, and enable interrupts.

- UIC (UFS InterConnect Layer): Issue the Link Startup command to bring up the link between the host and device and verify connectivity.

- UTP (UFS Transport Protocol Layer): Create the UTP command queues and enable UTP interrupts. Issue a NOP UPIU command to verify the transport path.

- Configure Gear and Lane: Negotiate gear and lane counts, then configure the link to operate at maximum bandwidth.

- UAP (UFS Application Layer): Register with CAM to begin SCSI-based initialization; CAM then scans the bus for targets and LUNs and delivers SCSI commands to the driver.

CAM (Common Access Method) is FreeBSD’s storage subsystem. It is organized into three layers: the CAM Peripheral layer, the CAM Transport layer (XPT), and the CAM SIM layer. After initialization, the UFS driver creates a SIM object with cam_sim_alloc() and registers it with the XPT via xpt_bus_register(). The XPT then scans the bus for targets and LUNs to discover SCSI devices. When it finds a valid LUN, it calls cam_periph_alloc() to create and register a Direct Access (da) peripheral in the CAM Peripheral layer.

With the Direct Access (da) peripheral registered, the CAM Peripheral layer automatically constructs SCSI commands when I/O to the UFS disk is requested. The driver’s ufshci_cam_action() handler, registered with the SIM, receives the CCBs that carry these commands, encapsulates them in UPIUs, enqueues them on the UTP queue, and on completion calls xpt_done() to notify the XPT.

Because CAM handles standard SCSI paths such as scanning, queuing, error handling, and retries, much of the required logic does not need to live in the UFS driver. The driver primarily forwards SCSI commands to the target device over UTP.

Queue architecture: SDQ and MCQ

One of the key design decisions was the queue architecture. UFS 4.0 introduced multi-circular queues (MCQ), which are conceptually similar to NVMe’s model. For backward compatibility, single doorbell queue (SDQ) support is also required, and the driver must select between SDQ and MCQ at runtime, since UFS 3.1 and earlier support only SDQ. To address this, I defined a function-pointer operations interface (ufs_qop) that abstracts queue operations so the implementation can be chosen at runtime. (MCQ is not yet implemented and will be added soon.)

Current status and future development plans

The UFS driver is under active development and currently implements a subset of UFS 4.1 features. My goal is to achieve full feature coverage, followed by power management and MCQ. At present, supported platforms are limited to PCIe-based UFS host controllers, and I plan to add support for ARM system-bus platforms as well. I also aim to track and adopt new UFS specifications promptly as they are released.

Getting Started with the UFS driver

To test the UFS driver, you typically need hardware with UFS built in. Fortunately, QEMU allows development and testing without such hardware. This section shows how to emulate a UFS device in QEMU and exercise the driver. (UFS emulation is supported starting with QEMU 8.2.)

Prepare a FreeBSD snapshot image.

$ wget https://download.freebsd.org/releases/VM-IMAGES/15.0-RELEASE/amd64/Latest/FreeBSD-15.0-RELEASE-amd64-zfs.qcow2.xz

$ xz -d FreeBSD-15.0-RELEASE-amd64-zfs.qcow2.xz

Create a 1 GiB file to use as the backing device for the UFS Logical Unit:

$ qemu-img create -f raw blk1g.bin 1G

Launch QEMU with an emulated UFS device:

$ qemu-system-x86_64 -smp 4 -m 4G \

-drive file=FreeBSD-15.0-RELEASE-amd64-zfs.qcow2,format=qcow2 \

-net user,hostfwd=tcp::2222-:22 -net nic -display curses \

-device ufs -drive file=/home/jaeyoon/blk1g.bin,format=raw,if=none,id=luimg \

-device ufs-lu,drive=luimg,lun=0

On amd64, the GENERIC kernel config includes the UFS driver module (see sys/amd64/conf/GENERIC):

# Universal Flash Storage Host Controller Interface support

device ufshci # UFS host controller

To load the module explicitly, edit /boot/loader.conf:

ufshci_load=”YES”

After reboot, verify that the UFS device is attached as ufshci0/da0 via camcontrol:

$ camcontrol devlist -v

scbus2 on ufshci0 bus 0:

<QEMU QEMU HARDDISK 2.5+> at scbus2 target 0 lun 0 (pass2,da0)

<> at scbus2 target -1 lun ffffffff ()

Basic performance checks with fio:

$ fio --name=seq_write --filename=”/dev/da0” --rw=write --bs=128k --iodepth=4 --size=1G --time_based --runtime=60s --direct=1 --ioengine=posixaio --group_reporting

$ fio --name=seq_read --filename=”/dev/da0” --rw=read --bs=128k --iodepth=4 --size=1G --time_based --runtime=60s --direct=1 --ioengine=posixaio --group_reporting

$ fio --name=rand_write --filename=”/dev/da0” --rw=randwrite --bs=4k --iodepth=32 --size=1G --time_based --runtime=60s --direct=1 --ioengine=posixaio --group_reporting

$ fio --name=rand_read --filename=”/dev/da0” --rw=randread --bs=4k --iodepth=32 --size=1G --time_based --runtime=60s --direct=1 --ioengine=posixaio --group_reporting

QEMU is an emulator, so it is best for checking functional behavior. For performance measurements, I used my Galaxy Book S.

The Galaxy Book S has an Intel 10th-gen i5-L16G7 (1.4 GHz, 5 cores) and an internal UFS 3.1 device, which I upgraded to UFS 4.0 for the experiment (operating at HS-Gear 4 on a 3.1 host controller).

|

Queue Depth |

Sequential Read (MiB/s) |

Sequential Write (MiB/s) |

Random Read (kIOPS) |

Random Write (kIOPS) |

|

1 |

709 |

554 |

7.1 |

12.1 |

|

2 |

1,395 |

556 |

14.8 |

29.4 |

|

4 |

1,416 |

559 |

31.6 |

68.2 |

|

8 |

1,417 |

554 |

63.5 |

102.3 |

|

16 |

1,399 |

555 |

103.7 |

105.5 |

|

32 |

1,361 |

556 |

114.2 |

106.6 |

Table 1. FreeBSD UFS Performance

Depending on queue depth, sequential write peaks at 559 MiB/s, and sequential read reaches 1,417 MiB/s, which is highly competitive for mobile devices.

|

Queue Depth |

Sequential Read (MiB/s) |

Sequential Write (MiB/s) |

Random Read (kIOPS) |

Random Write (kIOPS) |

|

1 |

542 |

479 |

6.1 |

11.0 |

|

2 |

1,358 |

548 |

13.0 |

21.0 |

|

4 |

1,351 |

550 |

29.7 |

53.1 |

|

8 |

1,352 |

550 |

61.1 |

84.1 |

|

16 |

1,351 |

552 |

119.0 |

114.0 |

|

32 |

1,355 |

553 |

142.0 |

120.0 |

Table 2. Linux UFS Performance

Under the same conditions on Linux, performance is at a comparable level.

Conclusion

UFS is a rapidly evolving interface standard. The FreeBSD UFS driver likewise adds new features and is continually optimized to enable UFS across a variety of devices.

I hope this article encourages wider use of UFS on FreeBSD. Contributions to the UFS driver are very welcome. I’m grateful to the reviewers who helped make this possible, and I plan to continue contributing to the community.

Development of the ufshci(4) UFS device driver was supported by Samsung Electronics.

Universal Flash Storage on FreeBSD

Universal Flash Storage on FreeBSD